Pearl Meister Greengard Prize honors Australian geneticist

by TALLEY HENNING BROWN

(opens in new window)Women’s work. From left, Paul Greengard, Ursula von Rydingsvard, Suzanne Cory, Wafaa El-Sadr and Paul Nurse.

(opens in new window)Women’s work. From left, Paul Greengard, Ursula von Rydingsvard, Suzanne Cory, Wafaa El-Sadr and Paul Nurse.

This year’s Pearl Meister Greengard Prize recognizes Suzanne Cory, an Australian geneticist whose work has included significant revelations about the workings of the immune system and the pathogenesis of cancer. President Paul Nurse presented Dr. Cory with the prize, the sixth annual award, at a ceremony in Caspary Auditorium on November 5.

The Pearl Meister Greengard Prize was established by Paul Greengard, Vincent Astor Professor at the university and head of the Laboratory of Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience, and his wife, sculptor Ursula von Rydingsvard. Greengard donated the proceeds of his 2000 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine to Rockefeller University and, in partnership with generous supporters of the university, created the yearly award. Named in memory of Greengard’s mother, the prize was founded to honor women who have made extraordinary contributions to biomedical science, a group that historically has not received appropriate recognition and acclaim. Past recipients of the award include Elizabeth H. Blackburn of the University of California, San Francisco, and Carol W. Greider of The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, who won shares of this year’s Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their work involving telomeres and telomerase.

The 2009 prize recognizes Cory, a world-renowned geneticist and pioneering scientific leader. The first woman to serve as director of Australia’s prestigious Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, she has been an influential force in shaping science policy in her nation. Along with her colleague and husband Jerry Adams, Cory was instrumental in introducing gene cloning technology to Australian research by establishing the country’s first facility for cloning eukaryotic genes in 1977.

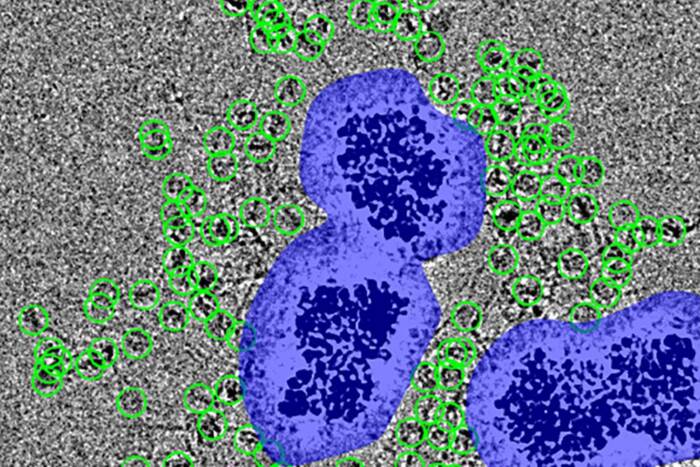

Research by Cory has yielded key insights in immunology and cancer biology. She and her colleagues made important contributions to understanding how immune system cells known as B lymphocytes assemble their antigen receptors by antibody gene recombination. In later work, they helped to elucidate how abnormal chromosome rearrangements can lead to the development of cancer. Cory and associates further broadened the molecular understanding of cancer through studies of mechanisms that promote tumor formation by interfering with the cell-death programs that normally protect against cancer. Her current line of research, examining the methods by which bcl-2 and other genes affect the cell death process, carries implications not only for cancer but for certain autoimmune and neurodegenerative diseases as well.

“I feel incredibly fortunate to have been part of such a revolutionary era in biology, but the best is still to come,” said Dr. Cory at the prize ceremony. “And I hope that in the future … at least 50 percent of those driving science will be women. It concerns me greatly that too many women continue to opt out, discouraged by the difficulties of combining career and family. We simply cannot afford this brain drain. That’s why I think the Pearl Meister Greengard Prize is so significant. In a sometimes hostile world, it stands as a rare beacon to inspire and encourage women of science.”

Cory received her Ph.D. in 1968 from the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, then the center of molecular biology research. Following postdoctoral research at the University of Geneva, she returned to Australia in 1971 and established her laboratory at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, where from 1988 to 2005, she was joint head, with Adams, of the molecular genetics of cancer division. From 1996 to 2009, Cory served as the institute’s first female director, a position from which she exercised a strong influence on Australian science and health policy. From 1992 to 1997 she was an international research scholar with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. She is a fellow of the Australian Academy of Sciences and of Great Britain’s Royal Society, which awarded her its Royal Medal. She is also a foreign associate of the United States National Academy of Sciences and was recently named a knight of the French Legion of Honor.

Special guest Wafaa El-Sadr, director of the International Center for AIDS Care and Treatment Programs at Columbia University and a world leader in the field of infectious diseases and public health, also spoke at the ceremony. Describing her two-plus decades of work with AIDS patients at Harlem Hospital and in Africa, she said, “What’s been rather remarkable is to have witnessed the women infected with HIV, how they’ve … overcome remarkable adversity in their lives — poverty, poor education, economic disadvantages — yet, often neglecting their own lives, they’ve been able to rise and take care of others in their community, and these women have been truly an inspiration to me…. I think the one factor that can shape the trajectory of a girl’s life in the world is education. It is very important that we support girls so they are able to stay in school, so they can achieve what they have the potential to achieve…. We must match these women’s courage with our own commitment to helping them achieve their dreams.”