Stem cells in hair follicles point to general model of organ regeneration

Most people consider hair as a purely cosmetic part of their lives. To others, it may help uncover one of nature’s best-kept secrets: the body’s ability to regenerate organs. Now, new research from Rockefeller University gets to the root of the problem, revealing that a structure at the base of each strand of hair, the hair follicle, uses a two-step mechanism to activate its stem cells and order them to divide. The mechanism provides insights into how repositories of stem cells may be organized in other body tissues for the purpose of supporting organ regeneration.

“The hair follicle is like a mini-dispensable organ,” says Elaine Fuchs, head of the Laboratory of Mammalian Cell Biology and Development. “Throughout our lifetime, each hair follicle undergoes cyclical bouts of growth, destruction and rest through an intrinsic stem cell population. It provides an excellent opportunity to investigate the molecular process of tissue regeneration and stem cell self-renewal.”

(opens in new window)

(opens in new window)

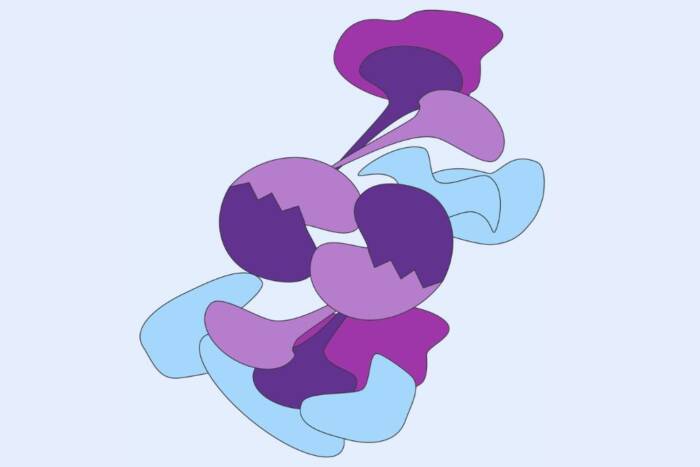

Deep roots. For a hair follicle to begin a new phase of growth, an elusive group of cells called the hair germ (bright red) must be activated. This progression of images shows that the hair germ begins proliferating (green) before other cells do, suggesting a two-step mechanism.

For a new round of hair growth to begin, stem cells in the hair follicle must receive a signal to divide. In response to this signal, the hair follicle regenerates first by growing downward through the skin’s middle layer, the dermis, and then producing the specialized cells that form the hair. After a period during which the hair grows longer, stem cells stop dividing, and the hair follicle gradually retracts again. There is then a period of rest and the cycle repeats.

Fuchs and her team have for several years been exploring the infrequently dividing stem cells located near the base of the hair follicle in a compartment known as the bulge. This time they focused on a much smaller cluster of often-ignored cells called the hair germ, located at the very bottom of this structure. Although little is known about the hair germ, scientists postulate that it emerges from the bulge at the end of the destructive phase of the hair cycle.

In their work, to be highlighted in the February 6 issue of Cell Stem Cell, Fuchs and her team scrutinized the hair cycle through the resting phase and discovered that during most of this time, both the bulge and the hair germ remain dormant. By isolating cells from both the hair germ and the bulge, they also confirmed that the two are molecularly very similar, suggesting that the germ does indeed originate from the bulge. The researchers believe, however, that toward the end of the resting phase, the hair germ gets activated to proliferate before the bulge. Moreover, the team showed that the activating signal comes from a structure known as the dermal papilla.

“We discovered that the dynamics of the hair follicle regeneration is a two-step process,” says Valentina Greco, a visiting postdoctoral fellow who, along with postdoctoral associate Ting Chen, spearheaded the project. “The hair germ, which is in constant contact with the dermal papilla, gets activated first and the bulge is then called to contribute later during growth.”

“Because the germ is in closer proximity to the dermal papilla, it may achieve a threshold of stimulatory signals sooner than the bulge,” explains Fuchs, who is also a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator. Previous work by her team has shown that two inhibitory signals, known as Wnts and BMP, are needed for hair follicle stem cells to activate. They have now identified an additional activation signal, a growth factor called FGF7, that is made by the dermal papilla and steadily increases throughout the resting phase. “We think that FGF7 might contribute, along with the Wnts and BMP inhibitory signals, to coax the hair germ to divide and proliferate,” says Fuchs.

The dual organization makes sense, explains Greco, since unlike the bulge stem cells, hair germ cells respond and proliferate quickly but soon exhaust their proliferative potential. “This organization prevents depletion of the bulge stem cells, which are long-lived,” says Greco. “It also allows a rapid initial proliferation of the hair follicles.”

Fuchs and her team believe that this dual organization of the stem cell niche could apply to other organs. “It could be that the two-step process we’ve identified is needed to achieve optimal organ regeneration, not only in the skin but also in the blood and intestine,” says Greco. “These organs have slow- and fast-cycling cells — much like the hair germ and the bulge — and have the capacity to self-renew and regenerate.”

Cell Stem Cell 4(2): 155–169 (February 6, 2009)(opens in new window)