Virologist Jim Murphy dies at 85

by TALLEY HENNING BROWN

The scion of a long line of scientists, James Slater Murphy’s life was infused with the spirit of scientific inquiry from his earliest days. The fervor for and dedication to pure research that he evinced in his later life were a hallmark of his association with Rockefeller University. Dr. Murphy passed away February 5, after a long battle with cancer, at his home in Deep River, Connecticut.

Born in New York City on June 2, 1921, Dr. Murphy was the son of Ray Slater, a descendant of Samuel Slater, an English textile entrepreneur, and James B. Murphy, a pioneer in the field of cancer biology and a member of The Rockefeller Institute who worked with Peyton Rous. Dr. Murphy’s interest in science began in childhood and he was the first high school summer intern at the Jackson Laboratory.

Dr. Murphy began studies at Princeton University, but when World War II erupted he enlisted in the Army, which sent him on to medical school without an undergraduate degree. He received his M.D. from Johns Hopkins University in 1945, and after his residency, also at Johns Hopkins, Dr. Murphy’s passion for research medicine led him to join the team of Nobel laureate in chemistry John H. Northrup, who had established a Rockefeller Institute laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley and was studying how bacteriophages form in bacterial cells. In 1955 he joined the New York campus of Rockefeller, as an assistant of the institute. He became associate professor in the laboratory of Igor Tamm in 1966. Dr. Murphy remained at Rockefeller for the rest of his career, becoming a member of the adjunct faculty in 1989 and associate professor emeritus in 1997.

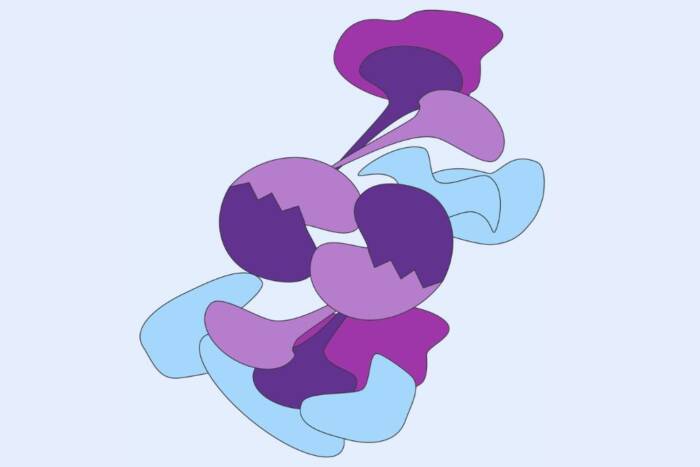

During his decades at Rockefeller, Dr. Murphy’s research covered virology, genetics, bacteriophages and cytokines. A collaboration with fellow Rockefeller researcher Lennart Philipson led to the isolation of the enzyme that allows a virus to essentially “drill” through a cell wall so that it can enter and use the cell’s synthesizing mechanisms. Dr. Murphy and his colleagues also used the first electron micrograph to show the influenza virus erupting through a cell wall. In later years, he was one of the first in his field, ahead of many younger scientists, to create computer-generated mathematical models to study questions concerning cell division and the synthesis of cellular DNA.

Dr. Murphy is survived by his second wife, Victoria Murphy, five children and several grandchildren.