Inside the brains of hungry worms, researchers find clues about how they hunt

When engaged in local search, C. elegans frequently change the direction in which they are wiggling. As a result, they end up scanning the same region over and over again.

Perpetually hungry, worms are strategic when it comes to searching for food. The microscopic roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans, or C. elegans, is known to spend up to 20 minutes seeking out snacks in its immediate surroundings before endeavoring to look elsewhere. Now, Rockefeller scientists have identified circuits in the C. elegans brain that underlie this behavior. In a new study, published in Neuron(opens in new window), the researchers describe neural mechanisms responsible for local search, showing that this response can be triggered by either smell- or touch-related cues.

Looking for grub in all the wrong places

C. elegans feed on bacteria. And when their environment is teeming with edible microbes, they needn’t move much to remain sated. But when food availability decreases, the worms start wiggling around a bit. First, they extensively search the area in which they last encountered sustenance, circling a small region for 10 to 20 minutes. Eventually, however, the worms widen their search perimeter—a strategy that resembles, and is possibly related to, some aspects of human behavior.

“If you lose your keys, you first search locally: in your wallet, then in your coat, and other nearby places. And you do this repeatedly,” says Cori Bargmann, the Torsten N. Wiesel Professor. “But if that doesn’t work, at some point you begin searching a broader area.”

The switch from local to global search has been observed in hungry insects, reptiles, fish, and mammals, suggesting that it may represent a conserved foraging strategy. With a uniquely small and well-characterized nervous system, C. elegans provided Bargmann and her colleagues with handy tools to study the basic brain mechanisms driving this behavior.

Munching on microbes

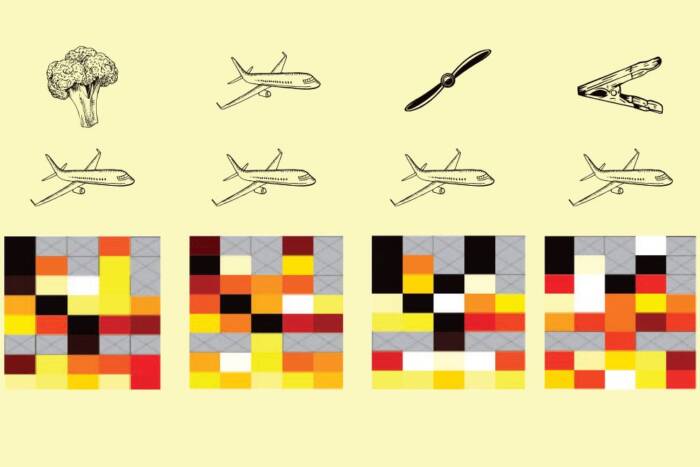

To identify cellular components involved in local search, biomedical fellow Alejandro López-Cruz first analyzed the genes of C. elegans mutants that failed to produce this behavior—worms that skipped the whole “local” phase and proceeded directly to global search. These animals, he discovered, had a defective form of a protein known as MGL-1, a receptor for the neurochemical glutamate. Additional experiments showed that MGL-1 receptors are found on two C. elegans neurons involved in detecting food: one called AIA, which receives input from chemosensory cells sensitive to food odors; and another called ADE, which is connected to mechanosensory cells responsive to food texture.

Mechanosensory neurons and ADE, the researchers found, are not physically connected to chemosensory neurons and AIA—suggesting that smell and touch responses function independently. Supporting these findings, the researchers showed that animals using only one sensory system can effectively detect and react to food removal.

“If you knock out glutamate from chemosensory and mechanosensory cells then you lose the behavior. But if you knock out only one, the animals respond normally,” says López-Cruz. “This tells us that there are two parallel and redundant pathways for detecting food.”

“That makes sense,” adds Bargmann, “because food is probably too important to survival to represent it in just a single form.”

Memorable meals

Investigating the longevity of local search, the researchers found that when mechanosensory or chemosensory neurons are stimulated, they act on MGL-1 receptors to modify the activity of ADE or AIA cells for minutes at a time. This cellular modification, in turn, triggers other neurons responsible for local search.

In short: When food goes missing, worm brain activity is altered for an extended period of time, yielding an extended search period. This process, says López-Cruz, seems to represent the formation of a memory related to changes in food availability.

“When we take the worm’s food away, we are essentially giving it a food-removal stimulus. The behavioral change that follows outlasts that stimulus by fifteen minutes, which is consistent with short-term memory,” he says.

The switch from local to global search, says Bargmann, seems to reflect the process of forgetting.

“A worm’s memory defines the period of local search,” she says. “And when it forgets, the animal moves on to longer-range exploration.”