Data suggest community involvement is the key to controlling infectious disease

The battles against infectious diseases are challenging enough in Western countries with stable infrastructure and deep-pocketed pharmaceutical firms. In an impoverished section of Latin America, they are much more difficult. But new research from Rockefeller University’s Joel E. Cohen suggests that the key to managing insect-borne illnesses in developing areas is a technologically simple, humanly sophisticated approach of sustained community outreach.

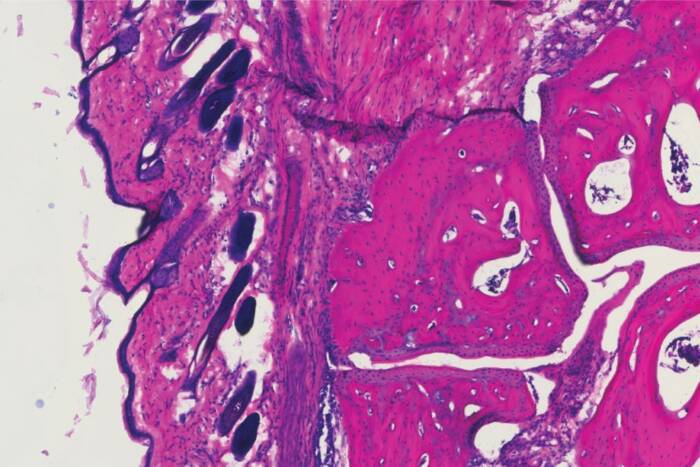

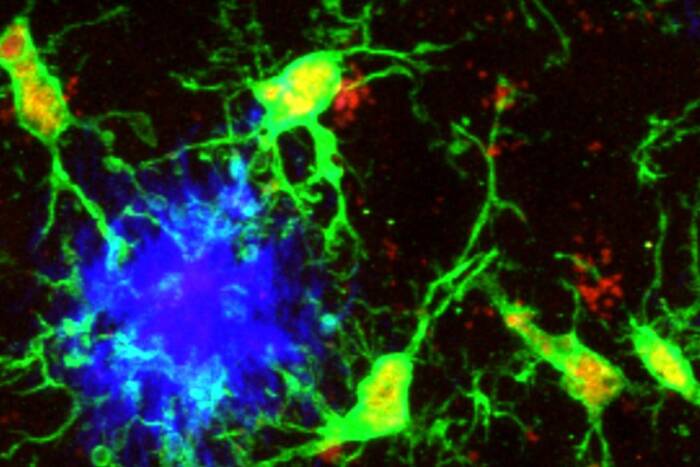

Cohen and his team, led by Ricardo Gürtler at the University of Buenos Aires and Uriel Kitron at the University of Illinois, used a “before–after” study to examine the effectiveness of methods to manage Chagas disease — a debilitating condition caused by the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi and carried by blood-feeding insects known as triatomines — in a region of Argentina known as Gran Chaco. Combining previously published evidence and new data they generated, the researchers assessed the results of sustained, supervised, community-based control by comparing the preintervention, reinfestation and sustained-intervention states of the study area. Data from the study, supported by the National Institutes of Health’s Fogarty International Center and a joint NIH/National Science Foundation grant, spanned over 20 years, from 1984 to 2006.

Efforts to control Chagas disease relied largely on a community-wide campaign of spraying insecticide to reduce the infestations of the bugs in homes, typically made of insect-friendly mud and thatch. A 1985 insecticide campaign reduced the prevalence of the disease in children but had no lasting effect: Seven years later, the bugs were back in force. In 1992, a more successful intervention largely suppressed the reestablishment of domestic bug colonies and finally led to the interruption of human T. cruzi transmission.

In their efforts to understand why the two campaigns had such different outcomes, Cohen and his colleagues made several findings.

A key component was the villagers’ walls. The researchers recruited home owners to gather evidence of domestic bug infestation and house invasion. Cohen and his colleagues found that infestation prevalence — the fraction of houses in which any infestation was detected — in well-plastered houses was consistently higher than in houses with cracks in the walls. However, the average number of bugs detected per household with average or poor walls was generally higher than the average number of bugs detected in households with good walls. “So, in houses with good walls, the householders were more attentive both to the bugs and to the walls but the average number of bugs detected, when any were detected, was lower than in houses with poor or average walls,” says Cohen.

More broadly, they found that community involvement — helping the villagers learn to combat the disease — is as important as spraying for controlling the disease over the long term. What works, says Cohen, who first became involved in this study in 1987, is collaboration between local people and expert supervisors who help the local efforts.

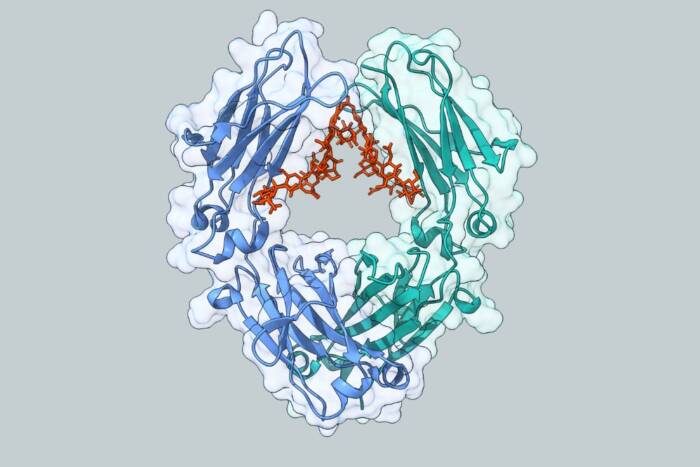

“High-technology solutions are not available to these poor people because the economic rewards do not justify investments by biotechnology companies in the development of vaccines and drugs,” says Cohen, who is head of the Laboratory of Populations at Rockefeller and Columbia Universities. “The only available alternative is to understand the ecology and behavior that sustain transmission and to empower the local people to interrupt transmission by behavioral change and ecological interventions.”

Because the infectious agent behind Chagas disease is present in forest-dwelling mammals in the southern United States the research also has implications for Americans. Indeed, the U.S. Red Cross recently instituted a screen for Chagas disease in blood donations. “Because people of the Gran Chaco migrate to cities, Chagas disease is potentially a threat in the cities, and people move between Buenos Aires and New York, for example, all the time,” says Cohen. It makes sense for wealthy and developing countries to collaborate in understanding and suppressing this disease, out of both self-interest and altruism.”

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104(41): 16194–16199 (October 9, 2007)(opens in new window)