Common immune cell marker shown to be off target

A marker that scientists have depended on for over 15 years to pick out a group of immune cells in the skin has been misidentifying them, Rockefeller University scientists report.

In order for scientists who study psoriasis and other skin disorders to understand the inner workings of disease, they use markers to label different types of cells to see how immune cells interact with other cells in the skin. But a surprise finding — confirmed when scientists noticed something unusual about pigment from patients’ tattoos — shows that one of these markers, Factor XIIIA, highlights an entirely different type of immune cell than previously thought. The research, published today in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, suggests that scientists may need to reevaluate the identity of cells that test positive for Factor XIIIA.

(opens in new window)

(opens in new window)

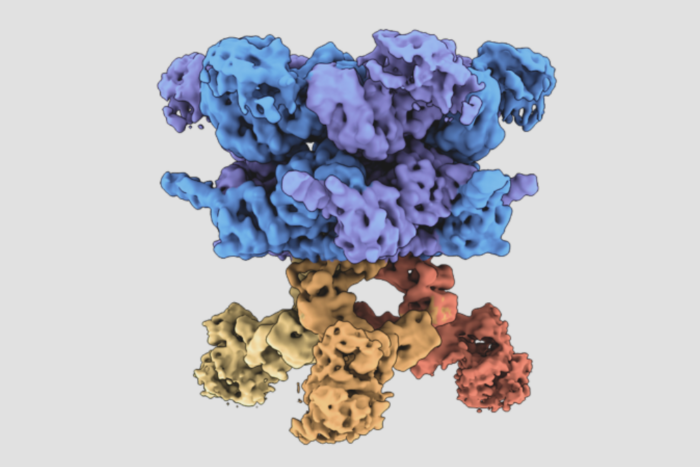

Color me wrong. The cellular marker CD11c (green) can be used to pinpoint populations of dendritic cells in skin, and researchers had also been using Factor XIIIA to identify dendritic cells. But in this cross section of healthy human skin, the red dendritic cells indicated by CD11c are visible as a completely separate population from the green cells, which turned out to be macrophages.

Dendritic cells — which are responsible for directing the immune system — play critical roles in maintaining healthy skin, and exploring how they work can help researchers better understand what happens when immune cells go awry and no longer distinguish “self” from “non-self.” Dogma among researchers is that there are three populations of dendritic cells in the dermal and epidermal layers of normal skin: Langerhans cells, plasmacytoid dendritic cells and myeloid dendritic cells. The new study shows that Factor XIIIA, which was used mainly to identify the myeloid variety, isn’t being taken up by any kind of dendritic cell at all but by white blood cells called macrophages.

These macrophages have small, skinny extensions called dendrites, the same features that gave dendritic cells their name. So it wasn’t too much of a stretch that, when they were first identified 15 years ago, the cells were thought to belong to the group of myeloid cells in the skin. “It was known that macrophages were present in the skin, but not that they were Factor XIIIA positive,” says study author Michelle Lowes, an instructor in clinical investigation in the Laboratory of Investigative Dermatology. But Lowes’s work — together with that of biomedical fellow Lisa Zaba, postdoctoral associate Judilyn Fuentes-Duculan and lab head and D. Martin Carter Professor in Clinical Investigation James Krueger — has shown that the marker long used to differentiate myeloid dendritic cells of the skin is singling out macrophages instead.

The researchers used two different markers that they believed would highlight populations of myeloid dendritic cells in the dermis and epidermis of the skin — CD11c and Factor XIIIA. But the markers identified two completely different sets of cells. When Lowes and her colleagues looked closely at the two groups, they saw that the CD11c-positive cells were indeed myeloid dendritic cells, but the Factor XIIIA cells had characteristics common to macrophages. One of the more unique of those was that, in skin biopsies taken from two subjects with tattoos, the skin had particles of tattoo pigment. While dendritic cells are too small to take up the large pigment molecules, macrophages have been known to do it. And the cells with the tattoo pigment were also the cells that took up Factor XIIIA.

Now that they’ve got a better idea of what the cell population of healthy skin is, the researchers’ next step is to classify the different sets of dendritic cells present in psoriasis. “Macrophages and myeloid dendritic cells have different functions,” Lowes says. “If we can understand what’s going on with these cells in psoriasis, it will give us alternative targets for therapy.”

Journal of Clinical Investigation: 117(9): 2517-2525 (September 4, 2007)(opens in new window)