Subset of dendritic cells could be used to fight infection

Although few people in the United States have reason to have heard of it, leishmaniasis is a parasitic disease that occurs in 88 different tropical and subtropical countries. Yet despite its prevalence, there is currently no vaccine to prevent transmission. Now, research by Rockefeller University scientists brings an effective vaccine one step closer, showing how it should be possible to recruit a specific subset of immune cells to do the lion’s share of the work.

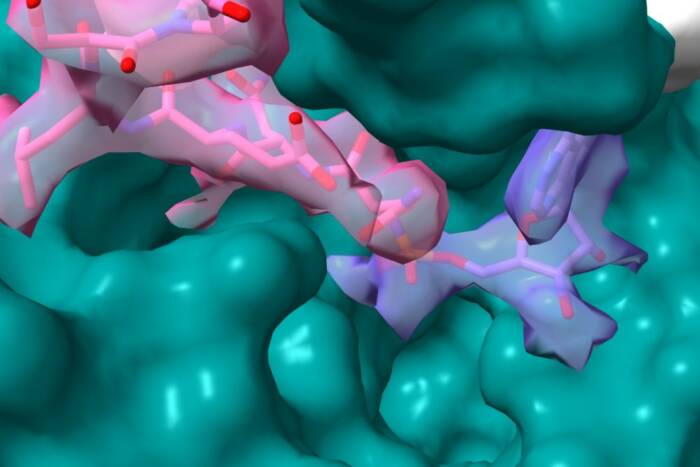

The key, it turns out, lies in the specificity of dendritic cells. Dendritic cells are responsible for presenting foreign substances to a second set of immune cells called T cells, thereby allowing the T cells to recognize the invader and hunt it down. Different dendritic cell subsets urge T cells to produce different cytokine proteins, and one of these cytokines — interferon gamma — is especially important in fighting off intracellular infections like leishmaniasis. Now a study published in the Journal of Experimental Medicine by Henry G. Kunkel Professor Ralph Steinman, head of the Laboratory of Cellular Physiology and Immunology, and postdoctoral associate Helena Soares, shows that targeting a leishmaniasis vaccine to a particular subset of dendritic cells should result in a substantial boost in immune response.

Steinman and Soares directed a protein from the Leishmania bacteria to two different subsets of dendritic cells: those that express a protein on their surface called DEC-205, and those that lack DEC-205 and express a different protein, 33D1. When presented with the Leishmania antigen LACK, the DEC-205 cells were capable of independently inducing T cells to produce interferon gamma. The 33D1 cells, however, elicited production of both interferon gamma and another cytokine called IL-4, which is known to inhibit interferon gamma activity. The team also found that the DEC-205 positive dendritic cells could even induce exclusively interferon gamma production in a strain of mouse known to produce IL-4 when presented with antigens.

This, Soares notes, is an important step for vaccine researchers. As with other dendritic-cell vaccine approaches the Steinman lab is investigating, targeting specific subsets of dendritic cells appears to control the quality of immune response. If scientists can create a vaccine that targets only the DEC-205 dendritic cells, they should be able to produce interferon gamma exclusively, with no inhibitory effect, and have a better shot at fighting off intracellular parasites like Leishmania. “Right now, people are working on vaccines without any targeting,” Soares says. “So you get interferon gamma production, but you also get IL-4 production. The vaccines aren’t optimized.”

Journal of Experimental Medicine 204(5): 1095-1106 (May 14, 2007)(opens in new window)