Preparing a multi-pronged attach: Different subsets of dendritic cells help expand the immune system's response

Dendritic cells coordinate and direct the body’s immune response, playing a crucial role in our ability to fend off disease. By processing molecules from invading pathogens — called antigens — they can present those molecules for other immune cells to recognize and attack. But researchers have only a limited understanding of precisely how those antigens get taken up and put on display. In findings that give a boost to vaccine research, Rockefeller University scientists show that different types of dendritic cells (DCs) process antigens differently.

(opens in new window)

(opens in new window)

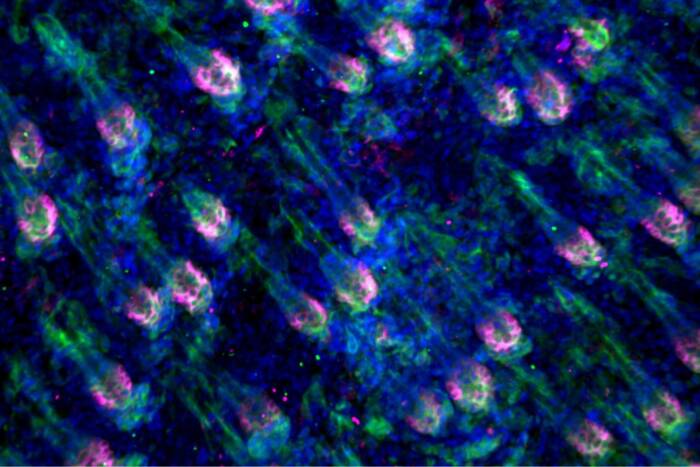

Preferential treatment. The mouse spleen holds two distinct subtypes of dendritic cells (DCs), each of which are located in different areas. DCs targeted by the DEC205 antibody (red) specialize in processing antigen for presentation by MHC class I molecules. Now, new research shows that DCs targeted by the 33D1 antibody (green) process antigen for presentation by MHC class II.

Scaffolding proteins on a cell’s surface, called major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules, present antigens for recognition by a specific group of immune cells known as T lymphocytes. MHC molecules have two predominant forms, class I and class II. Now, in research reported in a recent issue of the journal Science, Sherman Fairchild Professor Michel Nussenzweig and postdoctoral fellow Diana Dudziak show that the two kinds of DCs in the spleen vary in their ability to process antigens for the two MHC classes.

Each subset of spleen DCs can be distinguished by receptors on its surface: One has a receptor recognized by the DEC205 antibody, while the other has a newly identified receptor that’s recognized by an antibody called 33D1. “The DEC subset of dendritic cells is particularly good for processing antigens through MHC class I pathways,” says Nussenzweig, head of the Laboratory of Molecular Immunology and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator. This paper, which was a collaborative effort shared with Ralph Steinman, head of the Laboratory of Cellular Physiology and Immunology, “shows that the 33D1 subset is particularly efficient at processing for class II,” Nussenzweig says.

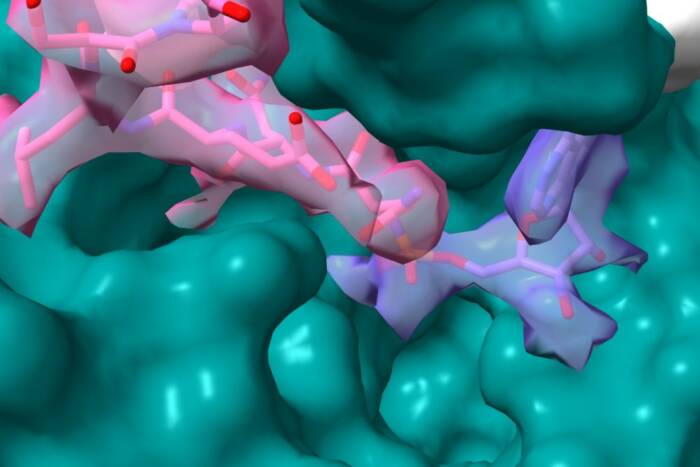

The two classes of MHC molecules interact with different immune cells: Killer T cells, which hunt down and attack foreign pathogens, recognize antigens presented by MHC class I; helper T cells, which prime killer T cells for the hunt, recognize antigens presented by MHC class II. By specifically targeting antigen to 33D1 dendritic cells and activating them with a T cell stimulating molecule, the researchers were able to enhance presentation on MHC class II, thereby increasing T cell expansion and the cells’ capacity to remember an antigen — something vital for potential vaccines, says Dudziak, the paper’s first author.

Developing vaccines that target DCs in vivo seems a very promising route, and one being pursued by a consortium of Rockefeller laboratories. This study gives them a new path to follow. “If there are different subsets of dendritic cells that process antigens differently in vivo,” Nussenzweig says, “then optimizing dendritic cell targeting vaccines may require targeting two different subsets of DCs.”

Science 315(5808): 107–111 (January 5, 2007)(opens in new window)