Scientists discover mosquitoes’ unique blood-taste detectors

When the tip of a mosquito’s stylet is exposed to a drop of blood (right), neurons activate that help her “taste” it.

The human blood meal is a favorite recipe for female mosquitoes. So drawn to its taste, they can’t help but bite—and in the process they spread diseases that claim 500,000 lives each year.

Yet scientists aren’t sure how the insects can even sense the complex taste of blood, or how they know that this, of all things, is something to gorge on. Nothing else, not even sweet nectar, makes them pump as ferociously as when they’re draining our veins. “When a female mosquito punctures the skin, she sucks so hard that the capillaries sometimes collapse. It’s a behavior she specifically reserves for blood,” says Leslie Vosshall, neuroscientist at Rockefeller.

Now Vosshall and her colleagues have discovered what turns on this powerful blood pump. In a study published in Neuron(opens in new window), the team describes a unique group of neurons in the female mosquito’s syringe-like stylet that don’t seem to care about simple tastes like sweet or salty. Rather, they activate only when sugar, salt, and other components of blood are all present at once.

“These neurons break the rules of traditional taste coding, thought to be conserved from flies to humans,” says Veronica Jové, a graduate student in Vosshall’s lab who led the study. “We knew that the female stylet was unique, but nobody had ever asked what its neurons like to taste.”

Homemade blood recipe

Vosshall, Jové, and colleagues began by perfecting their blood recipe. They started with sheep blood, which the mosquitoes swarmed to imbibe. When they exchanged the blood for sugar and saline solutions, the mosquitoes were no longer interested—even in the presence of heat and carbon dioxide, two cues that tell mosquitoes that humans are nearby. The scientists then served their picky eaters a mixture of glucose, salt, sodium bicarbonate, and adenosine triphosphate. The mosquitoes dined with gusto.

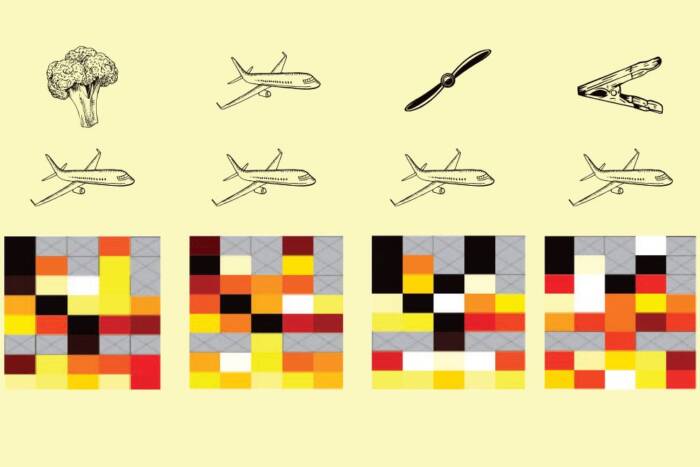

To see what’s special about the combination of these four ingredients, the researchers first tested how mosquito stylets responded to each component. “There are two neat rows of sensory neurons on both sides of the stylet,” Jové says. “We delivered just the tiniest microfluidic drop to the tip of the stylet, and recorded which neurons responded.”

Glucose, a sugar that is prominent in both nectar and blood, did not consistently activate any stylet neurons. The other three ingredients, which are unique to blood, each individually activated a specific group of neurons. But one prominent cluster of neurons did not respond to any individual ingredient; it only activated when the entire blood recipe was delivered at once—almost like being unable to taste coffee, milk, or sugar individually, unless all ingredients are stirred together.

The scientists call this group the integrator neurons because they seem to combine signals from several taste components, acting as the final arbiters in the decision to activate the pump for blood rather than nectar or water.

A syringe that can taste blood

Of the forty neurons lining a mosquito’s stylet, only half appear to be activated by blood. Future studies will examine the function of those remaining neurons, which may be involved in detecting unique flavors that appear only when the stylet pierces a capillary.

The findings have far-reaching implications for basic science. The study opens the door to further examination of a novel form of taste detection, and provides fascinating insight into how specialist species like mosquitoes develop unique feeding strategies. “The real beauty of this study is: how cool is it that we found a syringe that can taste blood?!” says Vosshall.