Mucosal Tissue Site of AIDS Virus Replication in Clinically Well HIV-Infected People

Virus appears to continuously replicate in tissues other than the lymph system

The mucous membranes that lie above the lymph glands of the throat can be a major site of HIV-1 replication in people infected with the virus that causes AIDS but who have not yet developed clinical symptoms, report scientists from The Rockefeller University and the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology(opens in new window)(AFIP) in the April 5 Science

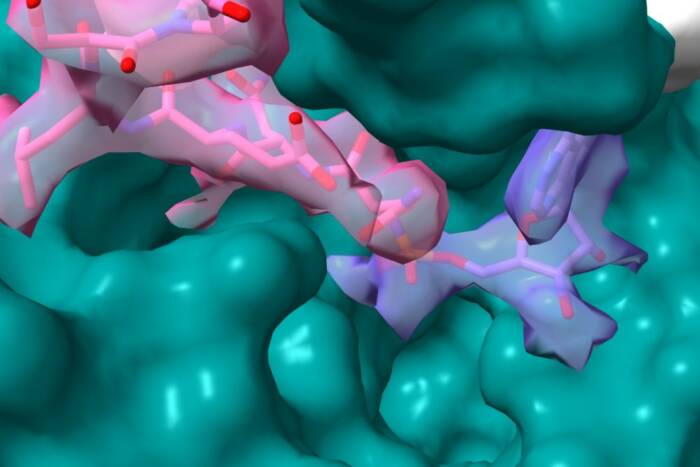

HIV-1 causes immune system cells to fuse to form a giant syncytia cell, which features several nuclei. Scientists from Rockefeller University and the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology found the syncytia in the mucous membrane of the adenoids, a previously unknown site of HIV replication.Photo by Sarah S. Frankel, M.D., and Bruce M. Wenig, M.D., of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology.

“By identifying a site in the throat’s mucous membranes where HIV-1 is so abundant in patients who are clinically well, we know that HIV-1 infection is not a slow or covert process,” says senior author Ralph Steinman, M.D., director of the Laboratory of Cellular Physiology and Immunology at Rockefeller and senior physician at the university’s hospital.

Previously, other scientists have had great difficulty in showing that HIV-1 grows in cells from the blood and inside lymph glands, but the new observations reported in Science point to the importance of understanding how the body’s mucosal surfaces and mucous membranes permit HIV-1 growth. These membranes line body cavities, such as the mouth and genital openings, as well as internal organs such as the respiratory tract and the digestive system.

The findings suggest a role for mucosal surfaces in several modes of HIV-1 transmission. “Infants who swallow virus from infected mothers during birth may be infected initially in the mucosal surface of the tonsils,” explains Steinman. “Also, inflammation of genital mucosal surfaces may promote infection after exposure to HIV-1 because dendritic cells and T cells, both involved in immune system responses, may interact in these tissues. Finally, in order for HIV-1 to be transmitted by blood, the virus may home to dendritic cells and T cells at mucosal surfaces like that of the adenoid.”

In the study, Steinman and his colleagues found that the driving force of HIV-1 replication in mucous membranes is the dendritic cell, discovered by Steinman and the late Zanvil Cohn, M.D., at Rockefeller in 1973. Dendritic cells are white blood cells with threadlike tentacles that capture bits of protein from infectious agents. Usually this capture leads to the development of strong immunity, the ability of the immune system to fight infections. However, HIV-1 takes advantage of the situation and uses dendritic cells to help itself multiply.

The mucosal surface of the adenoid has many shallow foldings that normally help infectious agents to access the underlying lymph tissue. In this fold, HIV-1 has infected the immune system's dendritic cells, marked by a dark stain. Photo by Sarah S. Frankel, M.D., and Bruce M. Wenig, M.D., of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology.

“From the evidence we gathered in laboratory experiments, HIV-1 infection looks more and more like a battleground in which dendritic cells control both armies,” says coauthor Melissa Pope, Ph.D., assistant professor at Rockefeller. “On the one hand, the dendritic cell promotes virus replication, while on the other, the cell likely induces a strong immune response to the virus.”

In the study, the AFIP scientists located HIV-1 from patients’ adenoids, lymph glands in the throat that are covered by a mucous membrane with many folds, which normally allow infectious agents to enter and stimulate the immune system. Specifically, the virus resided in syncytia cells within the membrane. Syncytia are unusual giant cells that form when certain viruses cause many immune system cells to fuse together. As a result, syncytia have many nuclei, which house genetic material. In a search to find what caused the syncytia, the scientists identified HIV-1 as the culprit.

“Before our study, syncytia have not been so readily seen during an HIV-1 infection,” reports coauthor Sarah S. Frankel, M.D., AFIP pathologist. “However, data from Dr. Steinman’s lab had suggested that syncytia would be the major sites for the multiplication and spread of HIV-1. With our finding of syncytia in the 13 patients we examined, the giant cells are far from a test tube curiosity.”

The investigators identified cells and syncytia in the adenoid’s mucosal surface that contained one HIV protein, p55gag, which serves as an essential scaffold for building new virus.

“From our laboratory experiments, we know that HIV-1 exploits mucosal dendritic cells and CD4+ T cells to form syncytia,” says Steinman. “The findings compel us to look within dendritic cells to identify important controls for virus multiplication. We think that studying dendritic cells will be important to designing HIV-1 vaccines, because it is within these cells that virus must be stopped.”

For the study, the research team examined tissue from 13 HIV-1-infected patients, aged 20 to 42, two of whom were female. Each had surgery between 1989 and 1995 to removed an enlarged tonsil. With the exception of one patient who refused testing, all patients had antibodies to HIV. Of these, two experienced AIDS symptoms, most denied high risk behavior and 11 did not know they had been infected.

Steinman, Pope and Frankel’s coauthors are Bruce M. Wenig, M.D., Allen P. Burke, M.D., Poonam Mannan, M.S., Lester D. R. Thompson, M.D., Susan L. Abbondanzo, M.D., and Ann M. Nelson, M.D., of the AFIP.

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, part of the National Institutes of Health, the Dorothy Schiff Foundation, the Norman and Rosita Winston Fellowship Program and the DirectEffect AIDS Research Program supported the study.