New probe technology illuminates the activation of light-sensing cells

Ultimately, Charles Darwin’s “endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful” can be boiled down to a scant 20 or so amino acids, the basic building blocks of life. From this parsimonious palette, nature paints the proteins that make up the wild diversity of life on earth, from the simplest bacteria to the most complicated structure in the known universe — the human brain. Now, in work published today online by Nature, researchers from The Rockefeller University reveal a new technique for tagging

(opens in new window)

(opens in new window)

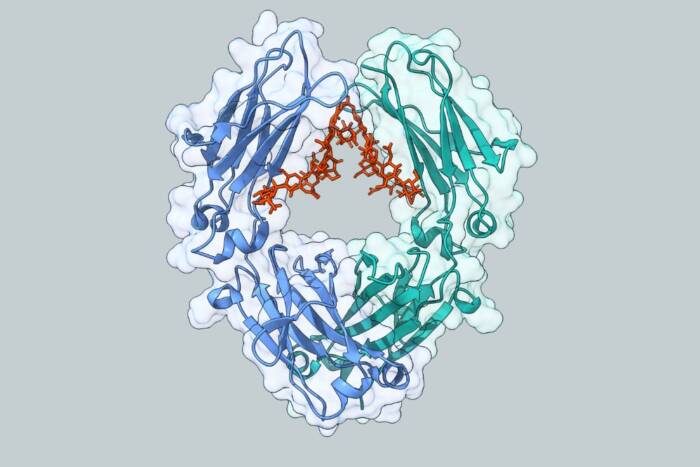

Seeing (infra)red. Scientists designed genetically encoded probes to examine the workings of the visual pigment rhodopsin (pictured above) with infrared spectroscopy. The probes revealed that light causes changes in the protein much faster than previously believed.

proteins with non-natural amino acids to scrutinize details about how they function.

The experiments in Nature yield new findings about rhodopsin, the light sensitive cell receptor that is crucial to dim-light vision, showing that light causes changes in the structure of the protein much faster than previously believed — on the order of tens of microseconds rather than milliseconds. Thomas P. Sakmar, head of the Laboratory of Molecular Biology and Biochemistry(opens in new window), and postdoctoral associate Shixin Ye, worked with colleagues in Germany, England, Spain and Switzerland, to combine a variety of genetic engineering techniques to introduce an amino acid, azidoF, a relative of phenylalanine, into several points on rhodopsin. The three-nitrogen-atom azido is an especially good probe for three reasons: In contrast to other tags, azido does not exist naturally in mammals, which makes it easier to “see,” or distinguish from other molecules in the cell; it is small enough to not interfere with a protein’s normal functioning; and it has chemical properties that make it a good handle on which to hang other molecules, like fluorescent probes.

In fact, the method could in principle be applied to place a fluorescent probe at any point in any protein in a mammalian cell. “The long-term goal is to label receptors in live cells and do single molecule fluorescent studies,” says Sakmar, who is Richard M. and Isabel P. Furlaud Professor. Such experiments could illuminate the minute functional differences that differentiate proteins the world over.

Similar approaches have been successfully used in bacteria, but last year, the researchers first showed that their method could be applied(opens in new window) to mammalian cells with such specificity and efficiency, the scientists say. Extensive genetic screening allowed the team to target the azido probes efficiently. They then confirmed the presence of azido with fourier transform infrared (FTIR) difference spectroscopy, which measures stretching frequencies of the atoms in the amino acids that make up a protein.

Because azido has a unique vibration frequency that is sensitive to its surroundings, the team was able to use the spectroscopic data to confirm structural changes rhodopsin undergoes in light versus dark. “What you want is a probe that doesn’t perturb the protein and one that can tell you something about its structure and function,” Sakmar says. “That’s what we have here.”

The scientists were able to see previously unobserved changes in the structure of rhodopsin, which is a model for the ubiquitous G protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), heptahelical, transmembrane receptors found in eukaryotic cells. There are more than 700 GPCRs in the human genome alone that constitute different signaling systems, activated by light-sensitive molecules, odors, neurotransmitters, hormones and pheromones. The scientists looked at regions of the GPCR, in this case rhodopsin, which are broadly shared or conserved among related receptors.

“We have found that the activation process that begins moving the helices apart — the earliest stage of signal transduction — is faster than predicted, maybe an order of magnitude faster,” Sakmar says. He hopes to use the technique to identify the mechanical components of the switch machinery that activate the receptors, he says, which are involved in a wide range of diseases and are the targets of many pharmaceuticals.

(opens in new window) (opens in new window) |

Nature online: April 11, 2010 Tracking G-protein-coupled receptor activation using genetically encoded infrared probes(opens in new window) Shixin Ye, Ekaterina Zaitseva, Gianluigi Caltabiano, Gebhard F. X. Schertler, Thomas P. Sakmar, Xavier Deupi and Reiner Vogel |