Experiments explain the events behind molecular ‘bomb’ seen in cancer cells

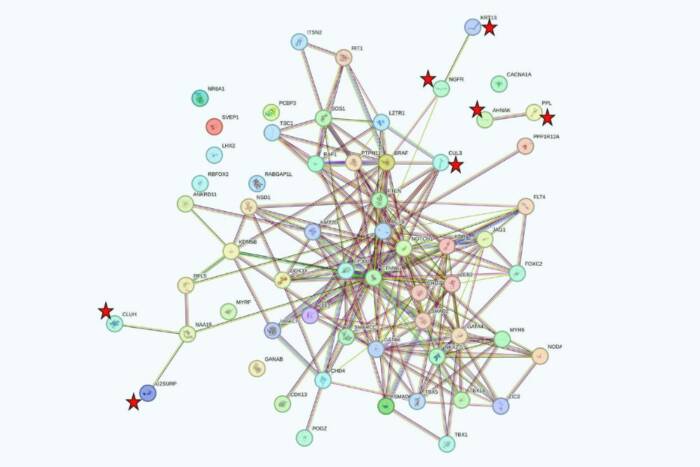

Since scientists have begun sequencing the genome of cancer cells, they have noticed a curious pattern. In many different types of cancers, there are cells in which a part of a chromosome looks like it has been pulverized, then put back together incorrectly, leading to multiple mutations. For years, this phenomenon puzzled scientists. But new research from The Rockefeller University suggests an explanation for this strange molecular explosion that serves as a precursor to cancer.

“The ‘old’ idea in cancer is that it arose from a first bad mutation, and then a second mutation, and a third, and so on, until the cells divide uncontrollably, leading to cancer,” says Titia de Lange, Leon Hess Professor and head of the Laboratory of Cell Biology and Genetics, who led the study. “This is a whole new view of how cancer can arise—a bomb goes off in part of a chromosome, and you get multiple mutations at the same time. These latest findings reveal the molecular details behind that bomb.”

The study, published December 17 in Cell, describes the cellular events leading up to the phenomenon dubbed chromothripsis. However, these insights into the origins of chromothripsis came from an investigation into another molecular event that can lead to cancer, known as telomere crisis.

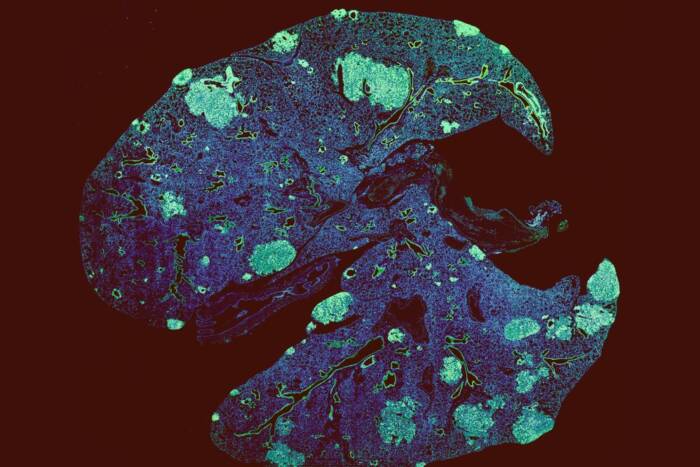

Telomere crisis results when the protective caps at the end of chromosomes, known as telomeres, become shortened as a result of cell divisions. With less DNA present in telomeres, it becomes harder to prevent separate chromosomes from attaching to each other. If those abnormal cells survive and continue to divide, they can give rise to cancer.

The researchers recreated telomere crisis in human cells by blocking the protein complex that prevents telomeres from fusing and disabling some of the molecular pathways that protect cells from turning cancerous. First author John Maciejowski, a postdoc in de Lange’s lab, filmed the events that followed.

For a long time, researchers believed that once two chromosomes fused together at their telomeres, they would eventually break apart during cell division. But the researchers found that’s not what happened at all. Instead, cells with fused chromosomes continue to divide with their chromosomes attached. Once division is complete and the new daughter cells try to move away from each other, the piece of chromosome they share becomes stretched, forming what’s known as a chromatin bridge. “I think of it as a balloon that’s been pinched in the middle, and the two outer circles are pulling away from each other,” says de Lange. “Or like a tug of war, and each cell represents the opposing team, and the rope gets stretched and stretched and stretched.” The chromatin bridge can reach 0.2 millimeters—an unheard of size at the cellular level.

Eventually, that bridge is broken down by one of the enzymes designed to target unfriendly DNA, such as that from viruses. And here, the researchers got a surprise—they discovered the enzyme that degrades the bridge DNA, TREX1, is normally present outside the nucleus that contains chromosomes. But as the two attached cells march away from each other, stretching the bridge DNA, that tension creates tiny tears in the membrane surrounding the nucleus, through which TREX1 enters and breaks down the chromatin bridge.

Once TREX1 causes the chromatin bridge to disintegrate, the two daughter cells spring away from each other. Each carries some of the bridge’s DNA fragments, which the cells then try to put back together. Some cells die from the trauma of this event, but others survive and divide, spreading the damaged DNA, which may contain shuffled portions, or have lost some of the genes that suppress cancer. In other words, this chain of events creates chromothripsis.

“The findings will hopefully help inform scientists’ understanding of the early molecular events that can lead to cancer, which may one day inform new methods to diagnose early stages of the disease,” says de Lange.

De Lange and Maciejowski collaborated on this project with Peter Campbell and Yilong Li from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in Cambridge, UK, as well as Nazario Bosco at Rockefeller.