Using magnetic forces to control neurons, study finds the brain plays key role in glucose metabolism

To learn what different cells do, scientists switch them on and off and observe what the effects are. There are many methods that do this, but they all have problems: too invasive, or too slow, or not precise enough. Now, a new method to control the activity of neurons in mice, devised by scientists at Rockefeller University and Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, avoids these downfalls by using magnetic forces to remotely control the flow of ions into specifically targeted cells.

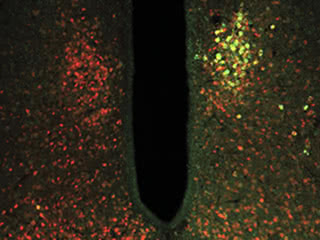

Open wide: The TRPV1 ion channel coupled with ferritin (green) was targeted to glucose-sensing neurons (red). Ferritin allows the ion channel to open in response to magnetic forces, activating or inhibiting the neurons. Changing the activity of glucose-sensing neurons had downstream effects on blood glucose metabolism.

Jeffrey Friedman, Marilyn M. Simpson Professor and head of the Laboratory of Molecular Genetics(opens in new window), and colleagues successfully employed this system to study the role of the central nervous system in glucose metabolism. Published online today in Nature, the findings suggest a group of neurons in the hypothalamus play a vital role in maintaining blood glucose levels.

“These results are exciting because they provide a broader view of how blood glucose is regulated—they emphasize how crucial the brain is in this process,” says Friedman. “And having a new means for controlling neural activity, one that doesn’t require an implant and allows you to elicit rapid responses, fills a useful niche between the methods that are already available.”

It may also be possible to adapt this method for clinical applications, says Jonathan Dordick(opens in new window) of Rensselaer. “Depending on the type of cell we target, and the activity we enhance or decrease within that cell, this approach holds potential in development of therapeutic modalities, for example, in metabolic and neurologic diseases.”

Magnetic mind control

Previous work(opens in new window) led by Friedman and Dordick tested a similar method to turn on insulin production in diabetic mice. The system couples a natural iron storage particle, ferritin, and a fluorescent tag to an ion channel called TRPV1, also known as the capsaicin chili pepper receptor. Ferritin can be affected by forces such as radio waves or magnetic fields, and its presence tethered to TRPV1 can change the conformation of the ion channel.

“Normally radio waves or magnetic fields, at these strengths, will pass through tissue without having any effect,” says first author Sarah Stanley(opens in new window) (now assistant professor of medicine, endocrinology, diabetes and bone disease at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai). “But when this modified ferritin is present, it responds and absorbs the energy of the radiofrequency or magnetic fields, producing motion. This motion opens the channel and allows ions into the cell. Depending on the ions flowing through the channel, this can either activate or inhibit the cells’ activity.”

This study is the first to turn neurons on and off remotely with radio waves and magnetic fields. TRPV1 normally allows positive ions—such as calcium or sodium—to flow in, which activates neurons and transmits neuronal signals. The researchers were also able to achieve the opposite effect, neuronal inhibition, by mutating the TRPV1 channel to only allow negative chloride ions to flow through.

“The modified TRPV1 channel was targeted specifically to glucose-sensing neurons using a genetic technique known as Cre-dependent expression,” says Stanley. “To test whether a magnetic field could remotely modulate these neurons, we simply placed the mice near the electromagnetic coil of an MRI machine.”

Blood sugar switch

Using this novel method, the researchers investigated the role these glucose-sensing neurons play in blood glucose metabolism. Hormones released by the pancreas, including insulin, maintain stable levels of glucose in the blood. A region of the brain called the ventromedial hypothalamus was thought to play a role in regulating blood glucose, but it was not possible with previous methods to decipher which cells were actually involved.

Friedman and colleagues found that when they switched these neurons on with magnetic forces, blood glucose increased, insulin levels decreased, and behaviorally, the mice ate more. When they inhibited the neurons, on the other hand, the opposite occurred, and blood glucose decreased.

“We tend to think about blood glucose being under the control of the pancreas, so it was surprising that the brain can affect blood glucose in either direction to the extent that it can,” says Friedman, who is also codirector of the Kavli Neural Systems Institute(opens in new window) at Rockefeller. “It’s been clear for a while that blood glucose can increase if the brain senses that it’s low, but the robustness of the decrease we saw when these neurons were inhibited was unexpected.”

Polar possibilities

The researchers’ system has several advantages that make it ideal for studies on other circuits in the brain, or elsewhere. It can be applied to any circuit, including dispersed cells like those involved in the immune system. It has a faster time scale than similar chemogenetic tools, and it doesn’t require an implant as is the case with so-called optogenetic techniques.

In addition to its utility as a research tool, the technique may also have clinical applications. “Although it is a long ways off, this technique may offer an alternative to deep brain stimulation or transmagnetic stimulation,” says Friedman. “We’d like to explore the possibility that this could provide some of the benefits of these without such an invasive procedure or cumbersome device.”

This work was funded by Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the JPB Foundation, the National Institutes of Health (GM095654 and MH105941), and a Rensselaer Fellowship (to J.S.) under an NIH predoctoral training grant (GM067545). Support for this project was provided by a grant from the Robertson Foundation.

(opens in new window)Nature, online: March 23, 2016 (opens in new window)Nature, online: March 23, 2016Bidirectional electromagnetic control of the hypothalamus regulates feeding and metabolism(opens in new window) Sarah A. Stanley, Leah Kelly, Kaamashri N. Latcha, Sarah F. Schmidt, Xiaofei Yu, Alexander R. Nectow, Jeremy Sauer, Jonathan P. Dyke, Jonathan S. Dordick, and Jeffrey M. Friedman |