DNA ‘barcoding’ reveals 95 species of life in NYC homes, students show

Two New York City high school students exploring their homes using the latest high-tech DNA analysis techniques were astonished to discover a veritable zoo of 95 animal species surrounding them, in everything from fridges to furniture.

Guided by DNA “barcoding” experts at The Rockefeller University and the American Museum of Natural History, 12th grade students Brenda Tan and Matt Cost of Trinity School, in Manhattan, also revealed a lot of apparent consumer fraud in progress, finding that the labels of 11 of 66 food products purchased at local markets misrepresented the actual contents.

The results will be reported in the January issue of BioScience magazine.

Among other things, Tan and Cost also found an invasive species of insect in a box of grapefruit from Texas as well as what could be a new species or subspecies of New York cockroach.

The work builds on the 2008 findings of two other Trinity School students, Kate Stoeckle and Louisa Strauss, who found one-quarter of fish they bought at markets and restaurants in Manhattan were mislabeled. Some labels hid endangered fish species but most misrepresented cheap fish species like tilapia sold as expensive species like tuna.

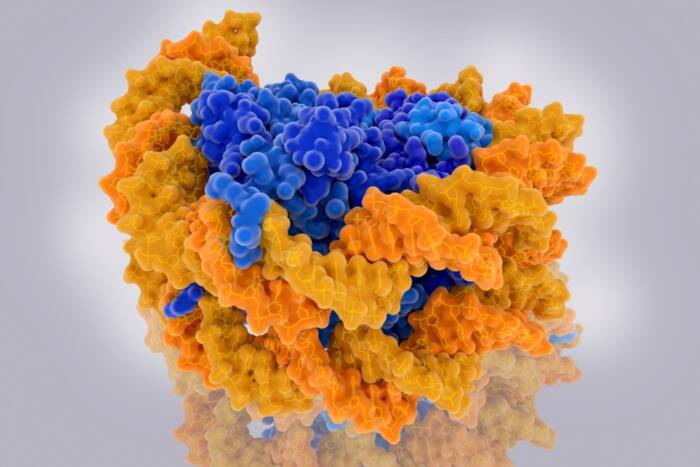

DNA barcoding technology identifies and distinguishes known and unknown species quickly, cheaply, easily and accurately based on a snippet of genetic code. Among the “mislabeled” food products identified by Tan and Cost using the technique:

• An expensive specialty “sheep’s milk” cheese made in fact from cow’s milk;

• “Venison” dog treats made of beef;

• “Sturgeon caviar” that was really Mississippi paddlefish;

• A delicacy called “dried shark,” which proved to be freshwater Nile perch from Africa;

• A label of “frozen yellow catfish” on walking catfish, an invasive species;

• “Dried olidus” (smelt) that proved to be Japanese anchovy, an unrelated fish;

• “Caribbean red snapper” that turned out to be Malabar blood snapper, a fish from Southeast Asia.

“You should get what you pay for,” says Cost. “We don’t know where it occurs, but most of the mislabeling involves substitution of something less expensive or desirable, which suggests it’s done for profit. Also, mislabeling exposes people with an intolerance or allergy to certain foods, or misleads people with dietary restrictions.”

“Knowing the sources of foods for pets like cats and dogs is important too,” says Tan. “And species identification can help protect the environment. Species that have protected status aren’t supposed to be sold. We think government agencies should start using these early versions of species identification tools to police the market, and the sooner the better.”

“This report signals to food and health authorities worldwide how simple and easy it is today to check and certify the origins of products in the market, crack down on fraudsters and protect both the health of consumers and depleted species,” says Mark Stoeckle, a member of the adjunct faculty in the Program for the Human Environment at The Rockefeller University.

Beginning in November 2008, the students accumulated a total of 217 household products and items and sent them to the American Museum of Natural History for analysis. Some 151 of them contained usable DNA, representing 95 different animal species — 60 vertebrates and 35 invertebrates. In addition to the cockroach, the students identified a long-legged house centipede — an alien species that originated in Europe — and an Oriental latrine fly found in the southern U.S.