Jill Donigian

B.A., Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey

B.A., Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey

TIN2 Assists TRF2 in Suppressing the ATM-dependent DNA Damage Response at Telomeres

presented by Titia de Lange

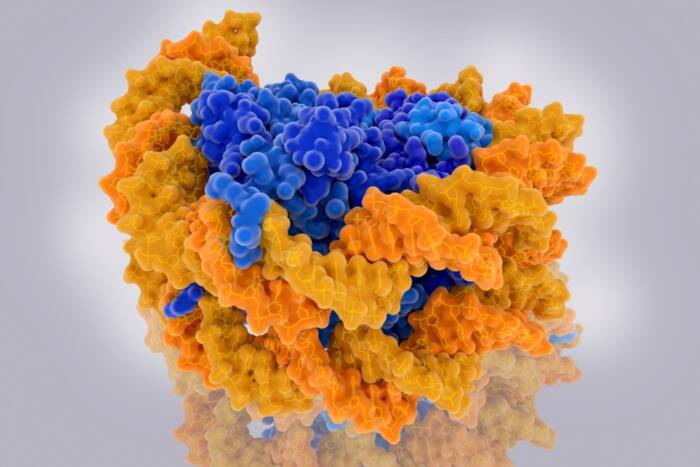

When Jill Donigian joined my lab, she already had extensive experience in biomedical research. Jill hails from New Jersey, where she went to college at Rutgers and worked with Nancy Walworth on the DNA damage response in fission yeast. She then did research in the laboratory of Nikola Pavletich at the Sloan-Kettering Institute, where she worked out the structure of SIRT2, one of the histone deacetylases called the sirtuins, which many of you know because of their proposed role in longevity. These enzymes form the basis of the hope that if you drink enough red wine, you may live longer, or if not, at least you had a good time.

Perhaps because her work on sirtuins had peaked Jill’s interest in how our cells age, Jill came to my lab to work on telomeres, another biological problem with a proposed link to longevity. As soon as Jill arrived, I realized that she was not only very good in doing experiments but that she is easily the most organized person I had met in my life. Frankly, Jill’s highly organized and spotless bench was initially a source of concern to me. I would walk by her bench at the end of the day and see nothing but clean, shiny surfaces and highly organized racks and pipettes. All other benches in my lab are jumbles of gels and tubes and notes scattered and piled up on top of each other. Jill’s model bench suggested to me that no experiments were taking place. Nothing is further from the truth. Jill produces data like a machine. But because she is so organized, she can do an impressive number of experiments in a short time yet somehow find the energy to clean everything up and enter her meticulous notes into her lab notebook at the end of the day.

In the years she has been in my lab, she has also managed to gently but persuasively impose order on others, leaving my lab much better organized than it was. Unfortunately, Jill’s powers did not extend to her thesis adviser, whose level of organization remains just one step removed from chaos.

Jill’s need to impose order on the world has helped her but has also been a source of aggravation for her. Things inside cells are often messy and usually do not align with the organizational aspirations of a graduate student. When one looks closely into any biological pathway, it is noisy, redundant and often more baroque than one would think necessary. Only when zooming in to the highest level of resolution achieved in crystal structures, or zooming out to the level of an overall pathway read-out, can we get a glimpse of the beautiful design of the inner workings of our cells. In between is the muddy arena of cell biology, and when Jill joined my lab, she had to deal with this morass. Jill has now cleanly emerged from this mud bath, thesis in hand, publications delivered, more papers to come, important aspects of telomere biology having yielded to her experimental force.

While Jill was working her way through the swamps of cell biology to extract the rocks of hard knowledge from the mud, Jill’s extracurricular activities included imposing order on her ever-growing household, which first was expanded with a husband, Dan Salomonsky, and then with a wonderful and wildly popular son, Max Thomas, who will celebrate today with his Ph.D. mom and M.D. dad and tomorrow, on June 13, will celebrate his first birthday.