Rockefeller postdoc named finalist for Eppendorf & Science Prize for Neurobiology

Max Heiman, a postdoctoral fellow at Rockefeller University, has been named a finalist in the eighth annual Eppendorf & Science Prize for Neurobiology competition. The international prize, established in 2002 by Eppendorf and Sciencemagazine, recognizes the most outstanding neurobiological research done in the past three years by a young scientist, as described in a 1,000-word essay. The winner and the two finalists will be honored with a ceremony this month at the annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience in Chicago.

The finalists will each receive an all-expense-paid trip to the neuroscience conference as well as $1,000 of Eppendorf products. Richard Benton, the grand prize winner for his essay “Evolution and Revolution in Odor Detection,” was a postdoc in Leslie Vosshall’s Laboratory of Neurogenetics and Behavior at Rockefeller from 2003 to 2007. He will also receive a personal gift of $25,000 and a trip to Eppendorf in Hamburg, Germany.

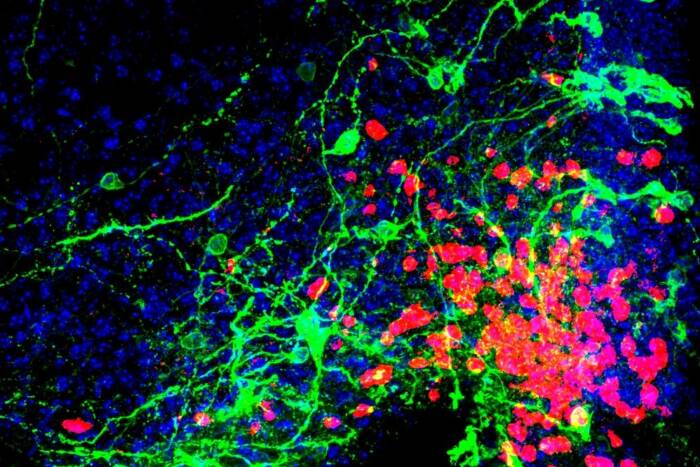

Heiman, who has worked since 2003 with Shai Shaham, head of the Laboratory of Developmental Genetics at Rockefeller, uses the microscopic roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans to study the assembly of neuronal shapes. In his essay, “The Brain That Nature Built,” he describes how a set of sensory neurons in C. elegans extend their dendrites to the animal’s nose: A neuron is born near the nose and drops anchor so that, as it crawls away, a dendrite is stretched out behind it. The broader implication of his work, which has also revealed two proteins that compose part of the anchoring machinery, is that the nervous system may assemble in part by using a map encoded by a constellation of such anchoring points.

“When I first began my postdoc at Rockefeller, I thought the brain would be built like a carpenter builds a house,” says Heiman. “But it is more like a spider dropping anchor and crawling down its web.” The mechanism, he says, underscores the idea that nature has an elegant way of building complicated structures from simple rules.

Heiman learned how to pipette in 1995 as a summer student with Steven A. Reeves at Massachusetts General Hospital; while there, he wrote Webcutter, one of the earliest online DNA analysis programs. He received a bachelor’s degree in biology in 1997 from Yale University, working with Frank Ruddle on homeobox genes in mouse development. As a graduate student with Peter Walter at the University of California, San Francisco, he identified the first protein implicated in membrane fusion — part of the yeast mating process that is analogous to sperm/egg fusion — and received his doctorate in biochemistry in 2002. He has been a fellow of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the Jane Coffin Childs Memorial Fund.

“Working with simple genetic systems such as C. elegans makes it possible to visualize one neuron at a time and understand the rules by which the nervous system self-assembles,” says Heiman. “It gives us ideas of how higher organisms are built.”