Edmund Ching Schwartz

B.S., University of Virginia

B.S., University of Virginia

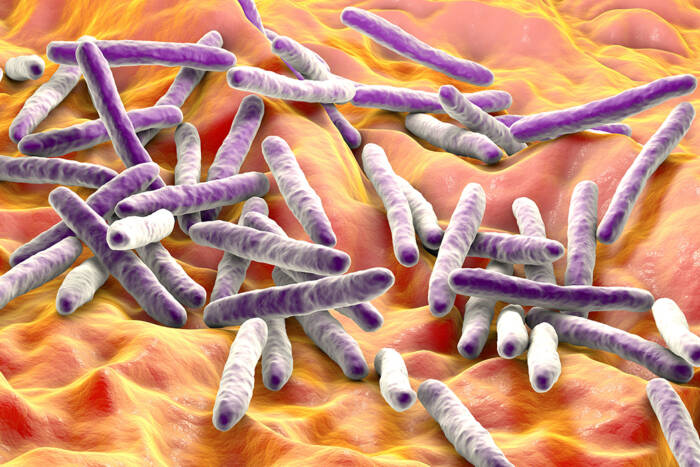

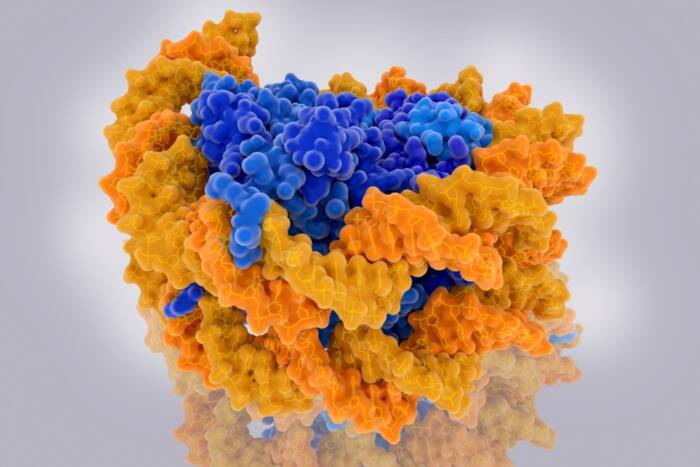

Controlling Bacterial Transcription: Regulation of the Sigma Factor

presented by Tom W. Muir

Ed Schwartz joined my group in the fall of 2001 following undergraduate studies at the University of Virginia. It soon became clear to me that Ed was an unusual talent. I can vividly recall the day he excitedly described to my group a new chemical technology he had conceived that would allow rapid activation of cytokine receptors in cells using small molecules. This would be a breakthrough, he predicted. I agreed; what’s more, I gave him my personal guarantee that his idea would work. This conviction was well founded, you see, since a very well-known Harvard chemist had spent over a decade using Ed’s technology in a series of quite famous and, of course, published experiments. Nonetheless, I was deeply impressed that Ed had thought this up independently, and so after I’d given him a quick tour of the university library, I unabashedly used every trick in the book to recruit him into my lab.

Now a few months later, Ed burst into my office with another one of his ideas. This time he wanted to chemically synthesize proteins inside a living animal, and by co-opting a process called protein splicing and by doing so, gain control over their function. Now I was pretty sure that no one had done this before, and to be honest, I thought he’d been spending a little too much time in the subterranean depths of the library. But Ed was adamant that he wanted to do this, and so because chemistry professors are famously averse to any creature with more than two legs, Ed forged a very fruitful collaboration with Mike Young’s lab to turn fruit flies into protein synthesis factories. Ed had to solve many protein engineering problems in trying to reduce his idea to practice, but with the kinks eventually worked out, he then showed that indeed his approach could be used to turn on the activity of an enzyme in a living fly in a rapid and tunable manner. Using his methods, one can simply feed a fly a drug and within minutes generate a protein from premade pieces, in other words, performing protein chemistry inside a living animal. This opens up many new experimental possibilities.

I didn’t think any of this was possible, and I think this serves as a beautiful illustration of the late Arthur C. Clarke’s first law, which, when translated from the original English, states “When a senior professor” — that would be me — “states that something is possible, he’s almost certainly right. When he states that something is impossible, he’s very probably wrong.” I would also note that in addition to the work in flies, Ed carried out a tour-de-force biochemical structural analysis of a bacterial sigma factor, which ultimately unearthed the mechanism by which a protein is autoregulated. In other words, Ed did enough work for two Ph.D.s.

Ed has now moved on to bigger and better things, as a postdoc in Richard Axel’s lab at Columbia, and being such an exceptional scientist, I know he’ll do well over there. However, we do miss him and his sometimes arcane sense of humor around the lab. Among other things, Ed has an ability to conduct an entire conversation using nothing but quotes from The Simpsons. This could be disconcerting, as when he quoted to me Homer Simpson as saying, “Facts are meaningless. You could use facts to prove anything that’s even remotely true.”