President Emeritus Joshua Lederberg dies at 82

by TALLEY HENNING BROWN

His career spanned 60 years, more than a few fields of science and a presidential legacy of dramatic expansion. And throughout it all, Joshua S. Lederberg was valued as highly for his role as mentor, colleague and member of a global community as for his groundbreaking research. At Yale, the University of Wisconsin, Stanford and ultimately Rockefeller, Dr. Lederberg approached his work with scrupulous attention to detail, highly imaginative approaches to problems and lifelong dedication to fostering community. Dr. Lederberg died February 2, at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital, at the age of 82.

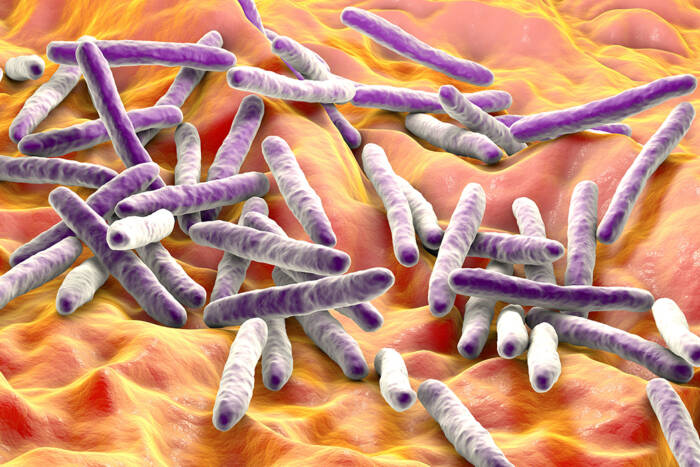

Dr. Lederberg, who grew up in New York City, was an undergraduate at Columbia College, working in the lab of geneticist Francis Ryan, when Oswald Avery, Colin MacLeod and Maclyn McCarty published their landmark 1944 paper on DNA transformation. With Dr. Ryan’s help, Dr. Lederberg began working with Edward L. Tatum at Yale University, where he looked for mutant genes in Escherichia coli, the common colon bacteria, and soon made his first famous discovery: that some bacteria have sex. It isn’t sex as humans know it, but “bacterial conjugation,” as he termed it, that accomplishes the mission of genetic exchange. This momentous discovery, made at the age of 22, was the subject of Dr. Lederberg’s Ph.D. It would later be recognized with the 1958 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, which he shared with Drs. Tatum and George Wells Beadle.

It was also the beginning of the burgeoning field of molecular genetics. Norton Zinder, head of Rockefeller’s Laboratory of Genetics, was Dr. Lederberg’s first graduate student at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, where Dr. Lederberg joined the faculty in 1947 and founded the department of medical genetics in 1957. Dr. Zinder’s experiments showed that certain bacterial viruses, called bacteriophages, can pick up bacterial genes and transfer them to the cells they infect — a second means of genetic exchange. “Josh recruited people all beginning work in new areas, and that seemed to be his recipe for success,” says Dr. Zinder. “Everywhere we turned we struck oil. You can’t imagine how excited I was … just figuring out how it all worked, completely on our own and with all this new stuff coming in as fast as it could. We rarely did an experiment that didn’t work and tell us something we didn’t know before.” It was also at the University of Wisconsin that Dr. Lederberg published several research papers with his first wife, Esther Lederberg.

Following the University of Wisconsin, Dr. Lederberg began his pioneering work in the fields of artificial intelligence and exobiology at the Stanford University School of Medicine, where he founded its department of genetics.

He was the fifth president of The Rockefeller University, serving from 1978 to 1990. Among his numerous contributions to the university’s growth, Dr. Lederberg oversaw the construction of the John D. Rockefeller Jr. and David Rockefeller Research Building and oversaw the creation of the highly successful University Fellows Program in 1985. Under the program’s auspices, 20 recruits have become tenured professors at Rockefeller.

James Darnell Jr., head of the Laboratory of Molecular Cell Biology and coauthor of the University Fellows Program with Dr. Lederberg and David Luck, was one of Dr. Lederberg’s closest colleagues. “I have been privileged to know at least fairly well all of the giants who created molecular biology in the last century and Josh Lederberg’s brilliance placed him high up in this group,” Dr. Darnell says. “If you excitedly began to tell him of your latest result, he grasped it completely before your last sentence was finished and he was ready immediately with the next experiment you should do.”

Throughout his research career, Dr. Lederberg remained a dedicated and trusted public policy adviser, serving nine U.S. presidential administrations and many world leaders on issues ranging from cancer and emerging infectious diseases to space exploration, nuclear and biological weapons disarmament, mental health and antimicrobial resistance. From 1966 to 1971, he wrote a weekly column for The Washington Post called “Science and Man,” commenting on timely, often controversial topics including science education, science and democracy, population control, intelligence testing, regulation of recombinant DNA technology and biological warfare. “Josh’s fine appreciation of the invisible colleges of the scientific disciplines that network the world made him sure that science could bridge America and Iran or Israel and Palestine,” said Jesse Ausubel, director of the Program for Human Environment at Rockefeller, speaking at Dr. Lederberg’s funeral February 5.

Dr. Lederberg retired from the Rockefeller presidency in 1990, becoming University Professor and head of the Laboratory of Molecular Genetics and Informatics, where he continued to conduct research. “As an emeritus president, Josh continued to be a wonderful campus citizen and a valued and trusted adviser to succeeding presidents, including myself,” says Paul Nurse, Rockefeller’s ninth and current president. “I am enormously grateful for the support, encouragement and friendship he afforded me.”

In addition to the Nobel Prize, Dr. Lederberg’s was awarded a National Medal of Science, a Presidential Medal of Freedom and many other prestigious awards, as well as membership in the National Academy of Sciences, the New York Academy of Sciences and the New York Academy of Medicine and foreign membership in the Royal Society, London.

“Josh died with his scientific boots on,” says David Thaler, associate professor and member of Dr. Lederberg’s Rockefeller laboratory. “He once said to me that when he is not there I should frame a matter in my mind and imagine what he would say about it. I replied that it is a treasure to interact with him precisely because what he has to say is likely to be an enlightened and delightful surprise.”

Dr. Lederberg is survived by his wife of 40 years, Marguerite S. Lederberg, children Anne Lederberg and David Kirsch and two grandchildren.