Visual neuroscientist named to Rockefeller’s faculty

Winrich Freiwald uses imaging techniques to study visual processing

by ZACH VEILLEUX

(opens in new window)With every glance, the human eye collects the equivalent of several hundred megapixels of data and passes it to the brain for processing. Understanding what happens next — how our brains organize this piecemeal information to let us perceive entire objects — is the life’s work of Rockefeller University’s newest faculty member, Winrich Freiwald. A cognitive neuroscientist who uses imaging techniques to study the parts of the brain responsible for visual processing, Dr. Freiwald has been named assistant professor and head of the Laboratory of Neural Systems. He will come to the university next winter following a short sabbatical at the California Institute of Technology.

(opens in new window)With every glance, the human eye collects the equivalent of several hundred megapixels of data and passes it to the brain for processing. Understanding what happens next — how our brains organize this piecemeal information to let us perceive entire objects — is the life’s work of Rockefeller University’s newest faculty member, Winrich Freiwald. A cognitive neuroscientist who uses imaging techniques to study the parts of the brain responsible for visual processing, Dr. Freiwald has been named assistant professor and head of the Laboratory of Neural Systems. He will come to the university next winter following a short sabbatical at the California Institute of Technology.

“There’s something striking about how we see the world. It’s a three-dimensional space inhabited by objects of shape, color, motion, depth, all combined,” says Dr. Freiwald. “We see things, not just stuff. But we can’t really explain this with our current understanding of the visual brain as a set of feature maps.”

Dr. Freiwald, a native of Oldenburg, Germany, developed his interest in neuroscience during high school. He received his Ph.D. from Tübingen University in 1998. After completing his postdoc, at the Max Planck Institute for Brain Research, he joined the Brain Research Institute and the Center for Cognitive Sciences at the University of Bremen, as a research assistant. He also conducted research at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, and then returned to Germany, where he has been head of the macaque brain imaging group at the Centers for Advanced Imaging and Cognitive Sciences in Bremen since 2004.

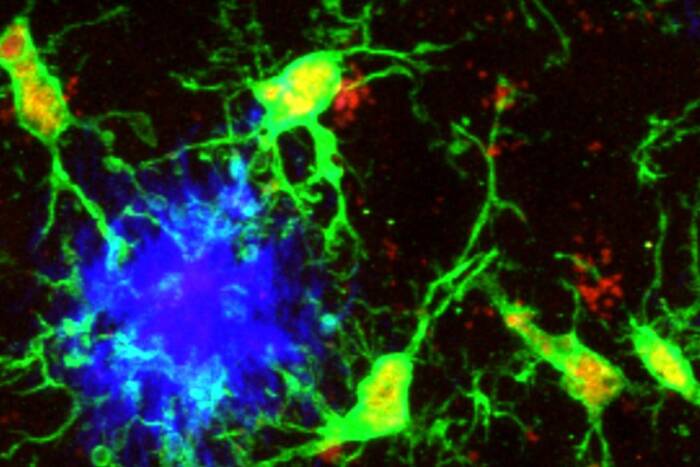

By using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to detect activity changes in the brains of macaque monkeys, as well as electrophysiological techniques, Dr. Freiwald has identified several regions, called patches, in the brain’s temporal lobes that are active during the processing of specific categories of objects. In particular, Dr. Freiwald is interested in the process by which the monkeys recognize faces, which is important for social reasons. His experiments have shown that neurons in one specific “face patch” respond whenever a monkey sees a face, while neurons in a second face patch respond only when it sees a certain face and neurons in a third face patch respond only when it sees a face in a certain orientation. Furthermore, Dr. Freiwald’s research suggests that these face patches are tightly connected to each other and form an entire face-processing network, with each patch devoted to a unique component of face processing.

“I think the face-processing system is just amazing, and presents us with a unique opportunity to study brain function. You can see it as a little biological machine that’s better at face recognition than any technical system to date and you can ask why it is so good. You can see it as a model system for understanding object recognition in general. You can use it as a model system to understand how different brain regions interact. And you can see it as an important building block of the social brain,” says Dr. Freiwald.

Dr. Freiwald is particularly interested in understanding how attention and other cognitive and emotional capacities modify visual processing. “Our work doesn’t stop with the visual aspects of faces,” says Dr. Freiwald. “Just a few synapses down the road you have areas that are critical to emotional, social and mnemonic aspects of brain function. Results in one area will inform new studies in other, connected areas.” The research, he hopes, could ultimately be useful in understanding diseases such as prosopagnosia — “face blindness” — and autism, a disorder characterized by impaired social interactions and face-recognition skills.

Rockefeller has a strong history of pioneering research on the mechanisms of visual perception. Torsten N. Wiesel, who is Vincent and Brooke Astor Professor Emeritus and a former president of the university, won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1981 for his studies of how visual information is transmitted to and processed in the visual cortex of the brain. Charles D. Gilbert, who is Arthur and Janet Ross Professor and head of the Laboratory of Neurobiology, focuses his ongoing research on understanding the specific role of the brain’s primary visual cortex in analyzing visual images and retaining visual memories.

“I’m delighted that Winrich will be coming to Rockefeller,” says Paul Nurse, the university’s president. “His work on visual processes is of great interest to scientists working to understand how our brains process information. His arrival at Rockefeller has also provided a good opportunity for the university to establish new imaging facilities that will be available to the entire university.”

Dr. Freiwald will conduct his studies at Rockefeller in collaboration with colleagues at the Citigroup Biomedical Imaging Center at Weill Cornell Medical College, which hosts the MRI machine on which Dr. Freiwald will conduct some of his work.