Evan Zane Macosko*

A.B., Harvard College

The Neural Circuitry of Social Behavior in Caenorhabditis elegans

presented by Cori Bargmann

Evan Zane Macosko, from the Tri-Institutional M.D.-Ph.D. Program, is a New Yorker, a Harvard graduate, a musician, a poet, a political idealist and a Renaissance man. With his education, Evan knew that in the 18th and 19th centuries, a debate raged among European philosophers on the proper balance between the rights of the individual and the needs of society. Opposing viewpoints were informed by opposing views of human nature as fundamentally good or flawed. On the utopian side, a vision of the perfect society was expressed by Jean-Jacques Rousseau in his essay The Social Contract:

“Each man, in giving himself to all, gives himself to nobody; and as there is no associate over whom he does not acquire the same right as he yields others over himself, he gains an equivalent for everything he loses, and an increase of force for the preservation of what he has.”

As an idealist, Evan used his Ph.D. research to study just such a perfect society. Broadening the philosophical debate, he studied a society not of humans but of nematode roundworms called Caenorhabditis elegans. Within its small world, C. elegans enacts the spectrum of viewpoints expressed by European philosophers. They are free: Different worms, armed with distinct genotypes, choose between social or individualistic lifestyles. They are flexible: Changes in the environment scatter the social groups to the four corners of their round plates. Further changes allow new groups to form.

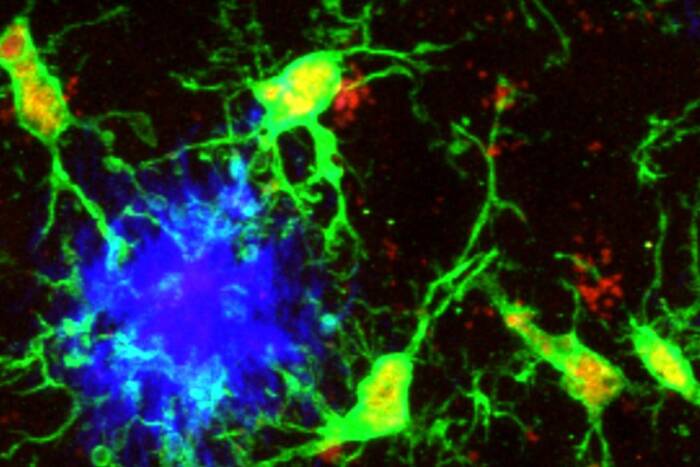

Evan, in his thesis work, defined the fundamental brain circuitry at the heart of these decisions. By tracking the genetic variation that makes individuals solitary or social, he identified a single pair of neurons that form the hub of the worm’s social brain. Genes, environment, stress and signals from other animals converge on this neuronal hub. What emerges from the hub is a decision, switching the animal between attraction to other animals and repulsion from them.

In a dazzling set of experiments, Evan activated neurons and silenced them; shut some lines of neuronal communication while leaving other lines open; watched the neurons signal; and watched the worm’s brain think as it responded to other worms. Evan’s work shows how a fixed brain can generate flexible behaviors by allowing information to flow down alternative synaptic pathways. This idea of flexible remodeling has explanatory power in complex nervous systems as well as simple ones.

These experiments were only some of Evan’s numerous accomplishments. In his imaginative and wide-ranging thesis work, he opened many avenues of research into animal social behaviors. Evan is now completing his M.D., but we look forward to the return of his remarkable creative intelligence to the world of research.