Nadya Dimitrova

Sc.B., Brown University

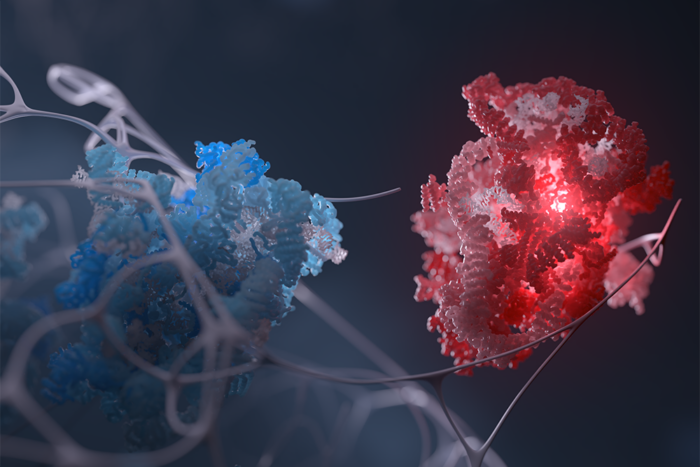

Characterization of a Novel 53BP1-dependent Mechanism That Promotes Nonhomologous End Joining of Deprotected Telomeres by Increasing Chromatin Mobility

presented by Titia de Lange

Nadya Dimitrova was born and raised in Bulgaria. Like many former Soviet countries, Bulgaria delighted in the freedom gained after 1989, which allowed Nadya to study abroad. Nadya chose training in biology at Brown University and then came to the Rockefeller graduate program with two main interests: neurobiology and cancer biology. Her interest in neurobiology led her to work with Paul Greengard before she joined my lab in the summer of 2003 to work on cancer-related issues.

Nadya initially joined our efforts to understand how telomeres solve the end-protection problem, but her project dragged her to what was then still a fringe effort in the lab, to understand the fundamental principles of how cells detect DNA damage and how DNA lesions are repaired. In part through Nadya’s work and her many journal club presentations in which she educated the lab (as well as her adviser) on this rapidly moving field, this issue is now a much more central aspect of our research.

Nadya’s experiments focused on the function of a DNA damage response factor, 53BP1, which was known to accumulate at DNA breaks but whose function was not known. In an elegant series of experiments, Nadya discovered that 53BP1 endows broken DNA ends with the ability to move through the nucleus. This rapid movement, detected by Nadya using ingenious live-cell imaging experiments, provides a DNA break with a greater chance of encountering another DNA end so that it can be repaired. This introduced a completely new concept, that of DNA dynamics, into the DNA repair field. Nadya’s efforts led to three papers, one in Nature, and more is in the pipeline.

Nadya’s adventures in the DNA repair arena went so far outside the scope of the lab that there came a moment where I realized that rather than Nadya coming to me for advice, I was going to Nadya for guidance on issues relating to DNA damage response. At the same time, Nadya must have realized that I was no longer a reliable source of information and suggestions to her. This is, of course, the final rite of passage for a student: going beyond what the adviser knows or can intuit and moving into a new area, navigating on her own. I don’t wish to give the impression that Nadya was isolated, though. While at the fringe scientifically, Nadya was at the center of the lab socially, at least in so far as the parties thrown by my lab can be said to have a center at all. I will miss that aspect of Nadya almost as much as her science. Although I must admit that I am a little relieved that there will be one less person at our parties trying to get me to drink more shots than I can handle.

Nadya defended her thesis in November 2008 and was honored earlier this year by the prestigious Harold Weintraub award. She has also received a Damon Runyon Postdoctoral Fellowship, which will support her current research in the lab of Tyler Jacks at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In Tyler’s lab, she has already repeated her trick of starting something entirely novel, and I wouldn’t be surprised if Tyler finds himself going to Nadya for advice, just like I did, rather than vice versa.