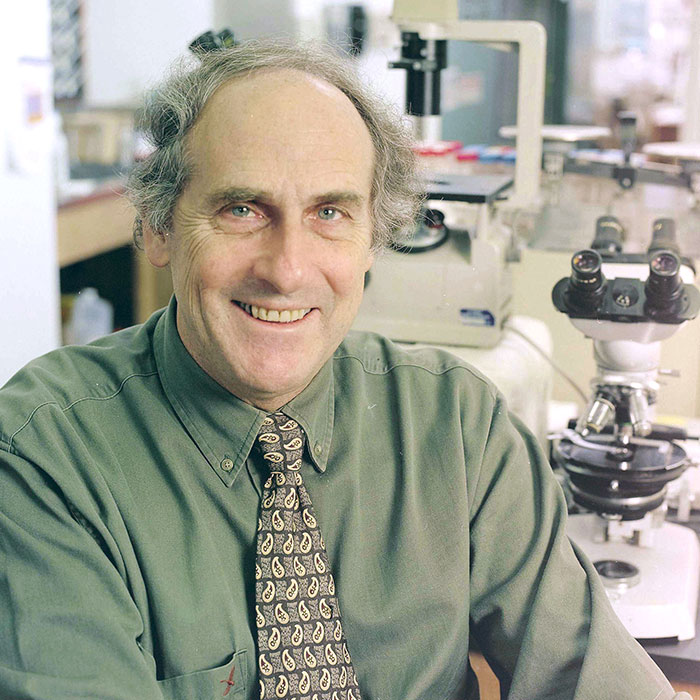

Nobel laureate Ralph Steinman dies at 68

Ralph Steinman, an immunologist who spent his entire career at Rockefeller and died just days before the Nobel Prize committee announced his name, passed away on September 30 after a four-and-a-half year battle with pancreatic cancer. Dr. Steinman, who discovered dendritic cells with Rockefeller immunologist Zanvil Cohn in 1972, spawned an entire branch of immunology devoted to understanding how the immune system is coordinated and how it learns to recognize infectious microorganisms and tumor cells. His recent work led to the development of an experimental human vaccine for HIV which began clinical testing last year.

Born in Montreal, Canada, in 1943, Dr. Steinman developed an interest in science at a young age, and he pursued it at McGill University and then Harvard Medical School. Although he trained to be a physician, he was drawn to research, and ultimately to Rockefeller, where he joined the laboratory of Dr. Cohn and James Hirsch — the Laboratory of Cellular Physiology and Immunology — in 1970. It was just a few years later that he made the landmark discovery that would define his scientific career.

Immunologists at the time had known there must be a cell that acted as a coordinator of the immune system — that would collect antigenic substances from foreign invaders such as bacteria and viruses and present them to B cells and T cells that carry out the dirty work of destroying the unwelcome guests. Scientists assumed this was primarily the work of macrophages. But while investigating the production of antibodies in the spleen, Dr. Steinman noticed an unusual cell that acted like a macrophage but didn’t look like one.

“Ralph coined the term ‘dendritic cell’ in 1973 because he thought the cells he discovered looked sort of like bare tree branches,” says Carol Moberg, a senior research associate who has worked in Dr. Steinman’s lab since 1987. “But over the years he often suggested alternate labels. He proposed ‘novel cell’ for its independence, ‘antigen presenter,’ ‘sentinel,’ ‘orchestrator,’ ‘controller,’ ‘nature’s adjuvant’ and, possibly inspired by his granddaughter’s favorite movie, Ratatouille, ‘a pilot light for a kitchen of fantastic immunological chefs.’”

For most of the 1970s, dendritic cells were, to put it mildly, underappreciated. Dr. Steinman himself was initially unaware of the significance of his finding. However, his dedicated examinations of the cell over the next several years revealed not a minor player but one that had been quietly running the show the whole time. Dr. Steinman showed that dendritic cells, not macrophages, are the main T cell-stimulating cells, and later demonstrated that they also stimulate B cells and NK cells. And the field of immunology reacted with silence and occasional ridicule.

“The idea that a new type of immune cell could be found in 1973 — in the era of molecular cell biology — simply by looking down a microscope seemed far-fetched, and the early criticism was relentless,” recalls Michel Nussenzweig, Dr. Steinman’s first student and current head of Rockefeller’s Laboratory of Molecular Immunology. “This put Ralph in the position of being not only the dendritic cell’s discoverer, but its advocate and cheerleader, and he spent much of his energy in those early years lobbying his colleagues to recognize its importance. That he ultimately succeeded is a testament to his forceful personality, energy and persistence.”

Dr. Steinman pursued the promise of dendritic cells for the rest of his career, and he built a great many collaborations with immunologists and scientists working in other fields. His in vivo studies in the 1990s found that immature dendritic cells position themselves at places in the body that are most vulnerable to invasion by microbes — the skin, the nasal passages and throat, the intestines, the genitals — and wait until they are needed. Then, as soon as a dendritic cell takes its first antigen prisoner, an incredible maturation process takes place in which its armor is strengthened and its antigen-presenting and signaling capabilities increase.

More recently, he focused a great deal of attention on the promise of dendritic cells to treat and prevent disease. The ability of dendritic cells to defend the body against autoimmunity might be channeled for use in the treatment of allergies, transplantations and autoimmune diseases like type 1 diabetes, multiple sclerosis and psoriasis. Moreover, the techniques developed by Dr. Steinman to work with dendritic cells effectively in a test tube have enabled the development of therapeutic dendritic-cell vaccines for various types of cancer and preventive vaccines for HIV.

“Ralph was led by the science and although he had his biases and direction, he always let the data drive things,” says Maggi Pack, a senior research associate who worked with Dr. Steinman for over 33 years. “He was objective, optimistic and never seemed to get discouraged.”

Eventually, with persistence, Dr. Steinman won not only the respect of his field, but also their commendation. In recent years he was the recipient of several of the most prestigious prizes in biomedicine, including the Gairdner Foundation International Award, the Albert Lasker Basic Medical Research Award and the Albany Medical Center Prize. And finally, this October 3, 38 years after his landmark publication, Dr. Steinman’s phone rang at 5 a.m. with the news that he would receive one-half of the 2011 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine — the ultimate recognition of his life’s work and vindication for all those early years when only he and a few close collaborators believed in it.

Sadly, the news came three days too late for Dr. Steinman to hear it.

Diagnosed with pancreatic adenocarcinoma in March 2007, Dr. Steinman’s original prognosis was poor. By the time it was detected — when Dr. Steinman went to see his doctor complaining of digestive distress and painless jaundice — the cancer had already spread beyond the pancreas. The one year survival rate for this type of cancer is just 25 percent and the average life expectancy about six months. But dendritic cells had the potential to fight exactly this type of aggressive tumor, and Dr. Steinman had access to brilliant collaborators and leading edge technology. He set about designing a course of therapy that he hoped would extend his life in a way that conventional chemotherapy might not be able to.

“He approached it the same way he approached any experiment,” says Sarah Schlesinger, research associate professor and head of Dr. Steinman’s clinical research program. “He worked with colleagues worldwide to arrive at a plan for treating the cancer, and he designed the therapy in a way that he hoped would allow us to learn something as he was being treated.” The Rockefeller University Hospital established a new clinical protocol, IRB and FDA approval was obtained, and Dr. Steinman formally became a clinical trial of one.

He had surgery (the tumor itself, once removed, was divided, preserved and sent to the labs of Dr. Steinman’s contemporaries all over the world to be used as the basis for individualized therapy) and received traditional chemotherapy, followed by a course of eight experimental immunotherapies in succession.

Dr. Steinman’s life post-diagnosis was a relatively healthy one, a fact that he also attributed to his immunotherapy. He felt well most of the time, and continued to work until the very end. He was vigorous enough to travel to conferences, and spent a great deal of time and effort to ensure that everyone in his busy lab had a path forward after he was gone. He was reviewing data — he was always eager to review data — just days before his death.

“We’ll never know for sure how much he was helped by the experimental therapies he received,” says Dr. Schlesinger, who was closely involved in his care. “Scientifically it’s just not possible to draw conclusions from a single patient. But he certainly enjoyed a longer and healthier life than the odds would suggest.”

The potential of dendritic cell-based vaccines is just now becoming apparent and clinical trials to better understand their therapeutic effects have begun in only the past few years. “Although Ralph did not live long enough to see his discovery win the Nobel, he did live to see vaccines based on his discovery used in real human patients, something that did not occur until after his diagnosis,” says Dr. Schlesinger. “He was thrilled to finally see the clinical impact of his work.”

“I had the opportunity to meet Ralph a number of times over the years,” says Russell C. Carson, chair of the university’s Board of Trustees. “Each time I did so, I was struck by not only his obvious intelligence but even more so by what a nice person he was. He had a keen interest in other people and he enjoyed talking about a wide variety of subjects. I’m sure a large part of his success in the scientific community came from his intellectual curiosity and his ability to both learn from and mentor others.”

“Ralph truly embodied the spirit of what sets Rockefeller apart,” says Marc Tessier-Lavigne, the university’s president. “He was a risk taker and a pioneer, who believed in his findings even when others did not, as well as a careful and precise scientist whose steadfast pursuit of the workings of dendritic cells led him to have an outsized impact on his field.”

“It will be a long time, if ever, before we feel that Ralph isn’t here,” says Dr. Pack. “His presence has been so powerful and his legacy will be so strong that a part of him will always live with us at Rockefeller.”