2016 David Rockefeller Fellowship awarded to third-year graduate student Lillian Cohn

by Alexandra MacWade, assistant editor

Lillian Cohn, a graduate fellow in Michel Nussenzweig’s Laboratory of Molecular Immunology, has been awarded the 2016 David Rockefeller Fellowship, given annually to an outstanding third-year student for demonstrating exceptional promise as a scientist and a leader.

The fellowship was established by alumni in 1995 as an expression of gratitude for David Rockefeller’s role in founding the university’s graduate program and for his commitment to its success. Mr. Rockefeller, who has served for more than 75 years on the university’s Board of Trustees, and celebrated his 100th birthday last summer, has said that few honors have meant so much to him as the creation of this award.

Ms. Cohn, who grew up in Seattle, initially planned to go to medical school. She majored in biology and was a pre-med student at Brown University, but as time went on, she found herself drawn more to lab research. “Patient care was still a priority to me, but I wanted to do science that could reach many people at once,” she says.

After graduating from Brown, Ms. Cohn worked at the biotechnology firm Genentech for two years. She knew Rockefeller well—her grandfather Zanvil A. Cohn was co-head of Rockefeller’s Laboratory of Cellular Physiology and Immunology until his death in 1993—and joined the graduate program in 2013.

“Rockefeller is an incredible place,” she says. As an undergraduate, Ms. Cohn enjoyed the open curriculum at Brown, which allows students to create their own programs of study. That same kind of flexibility attracted her to Rockefeller. “There are no departments or bureaucracy here. You find your own way, and the student is driving the program,” she says.

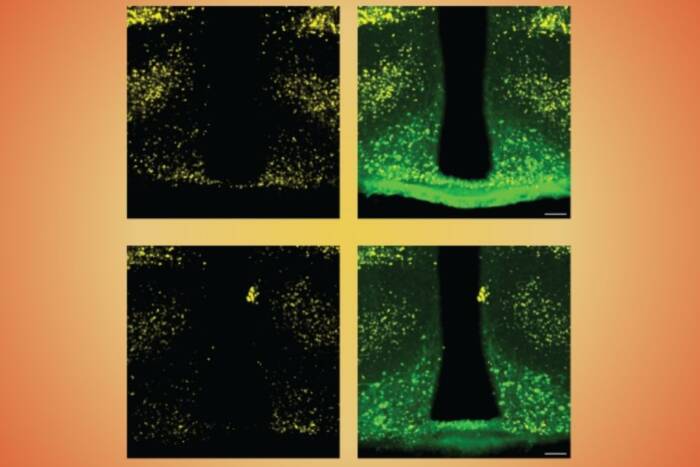

Much of the research in the Nussenzweig lab focuses on the biology of HIV or the development of new therapies against the virus, including broadly neutralizing antibodies and vaccines. Ms. Cohn’s work is focused on figuring out why there isn’t yet an effective cure for the disease.

Although HIV can be controlled with drugs, HIV-positive individuals will develop AIDS if therapy is discontinued. That’s because there’s a number of cells in their bodies that harbor HIV and remain undetected by the immune system. “These cells don’t get killed; they just hang out,” Ms. Cohn says. “If the therapy is stopped, they’re lying in wait, like sleeper cells.” Ms. Cohn is studying and characterizing these cells as a way to understand how to cure HIV.

Outside the lab, she is an enthusiastic volleyball player—she’s captain of a team that plays in a Manhattan league—and an active volunteer with New York Cares. She also volunteers in prisons; while in California, she was involved with the Prison University Project at San Quentin State Prison, teaching English literature and biology to inmates. “It was a transformative experience, and it helped me understand the power of education in the lives of people who had limited access to it before,” she says. Here in New York, she has taught incarcerated high school students.

Looking ahead, Ms. Cohn hopes to have her own lab. It’s a goal that not only reflects her love of science but also the obligation she feels to help other aspiring scientists, especially women. “It’s hard to be a woman in science,” she says. “I’ve had amazing women mentors who have inspired me every step of the way, and I want to pay it forward.”