In brief: A close look at how HIV-fighting proteins slow the virus down

When the HIV virus attacks, it inserts a permanent copy of its genetic material into the infected person’s genome. But the body has evolved mechanisms to fight back, including a cellular process that mutates the viral DNA, slowing the disease.

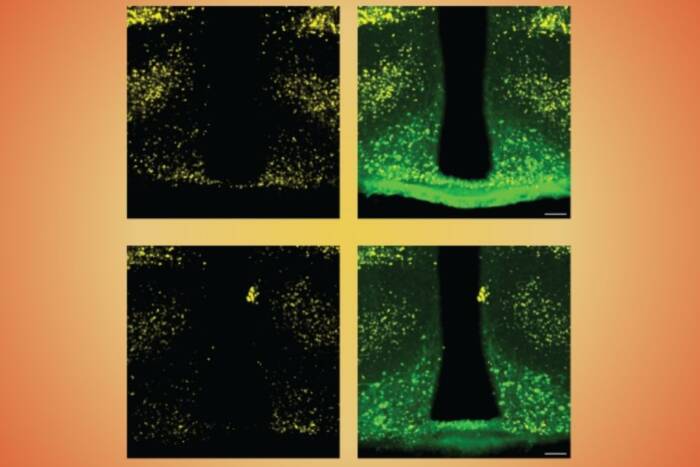

Now researchers from The Rockefeller University and the University of Michigan have provided fresh insight into how a protein called APOBEC3H (or A3H, for short) helps cells recognize the virus as an invader, an important step in accomplishing the defense. When HIV leaves an infected cell, A3H sneaks into viral particles by hitching a ride on strands of RNA that make up the viral genome. That RNA is then copied into DNA, and before it slots itself into the human genome, A3H mutates it.

In studying the molecular structure of A3H, Theodora Hatziioannou, a research associate professor in Paul Bieniasz’s Laboratory of Retrovirology, provided clues about how the protein uses RNA binding to get into the virus, and how it can subsequently mutate the newly-formed DNA.

The scientists hope that by better understanding how this and other defender proteins work, they’ll be able to devise new therapies and treatment strategies for HIV.