Year in review: 10 science stories to remember

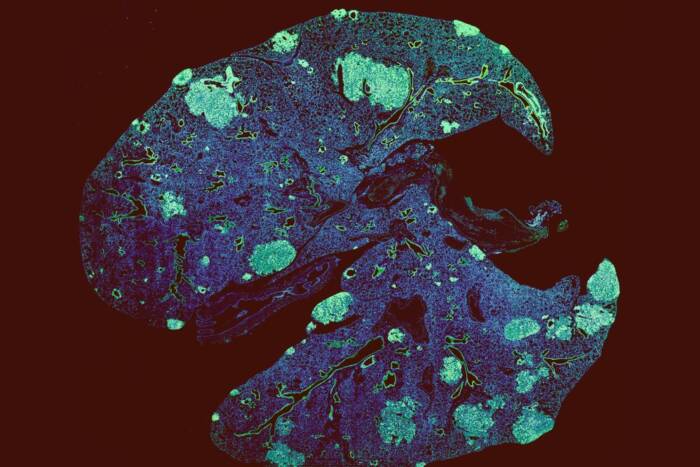

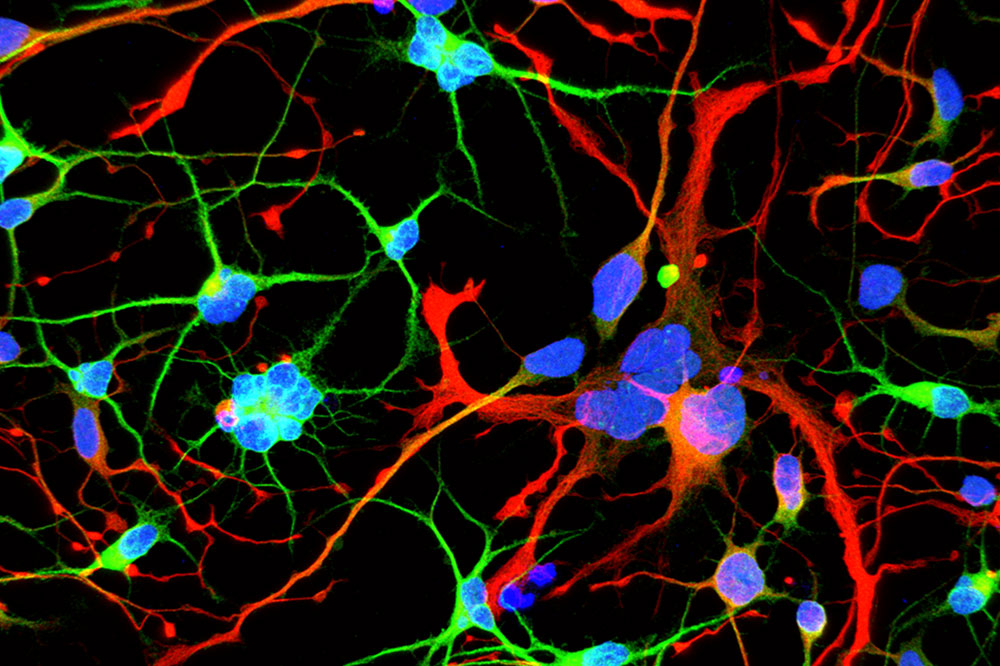

Among the year’s findings was the discovery that young neurons afflicted by Huntington’s disease have multiple nuclei (blue) within the same cell.

The coming of a new year calls for reflection and good tidings. Fortunately, Rockefeller scientists excel at reflecting; and their good tidings come in the form of riveting research. So, as the year comes to an end, here is a look back at 10 of the most memorable science stories of 2018.

The year started strong with research from the lab of Ali H. Brivanlou, who in January demonstrated that signs of Huntington’s disease can be detected in the developing embryo—a finding that may lead to new strategies for managing the disease. And in February, Cori Bargmann identified chemical messengers that underlie individuality in microscopic roundworms, proving that even simple critters can have quirks.

#1: Uncovering the early origins of Huntington’s disease

#2: Why we need weirdos(opens in new window)

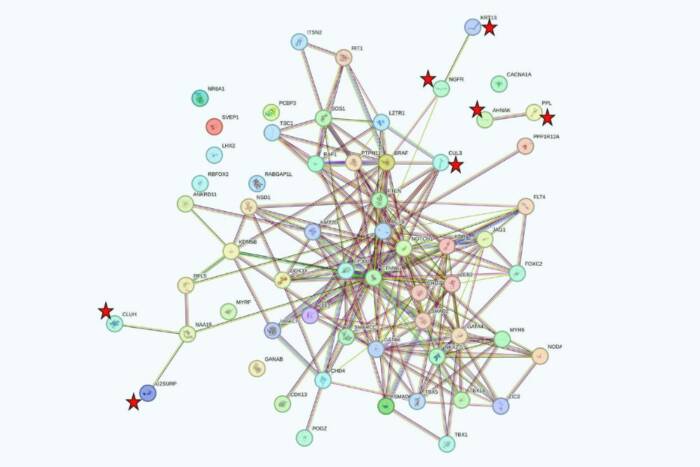

Rockefeller researchers also made substantial strides in developing treatments for serious illnesses. Michel C. Nussenzweig, Marina Caskey, and their colleagues showed that combination antibody therapy can suppress HIV for months at a time. Sohail Tavazoie and Daniel Mucida developed a new strategy by which to combat cancer cells using the body’s immune system. And Kivanç Birsoy found that depriving tumors of oxygen impedes their growth.

#3: In clinical trials, new antibody therapy controls HIV for months after treatment

#4: Bad news for cancer cells and their cronies(opens in new window)

#5: A new tactic for starving tumors

Elsewhere on campus, scientists continued to expand our grasp of insect biology. The lab of Leslie B. Vosshall created a genome blueprint for the mosquito Aedes aegypti—a crucial step toward preventing the diseases they carry. Daniel Kronauer and his colleagues showed that, in ants, group living has its perks. And Vanessa Ruta’s lab shed light on how fruit flies find suitable mates.

#6: Mosquito genome opens new avenues for reducing bug-borne disease

#7: Ant-y social: study of clonal raider ants reveals the evolutionary benefits of group living

#8: Deep in the fly brain, a clue to how evolution changes minds

Accompanying insights from tiny organisms were fascinating findings about the brains of our close relatives, macaque monkeys. Charles D. Gilbert found that as these animals learn a new visual task, the brain area devoted to vision undergoes significant changes. Studying the same species, Winrich Freiwald identified a brain region that could be an evolutionary precursor to the structure responsible for human speech.

#9: To see what’s right in front of you, your brain may need some rewiring

#10: Studies reveal possible origin of human speech

Macaque monkey. (Photo by Stephen Shepherd)

Happy reading, Happy Holidays, and stay tuned for another year of spectacular science.