Rockefeller immunologist receives Lasker Award for Basic Medical Research

This year’s Albert Lasker Award for Basic Medical Research, the most prestigious American prize in science, honors Rockefeller University’s Ralph M. Steinman, who discovered dendritic cells, the preeminent component of the immune system that initiates and regulates the body’s response to foreign antigens. The award will be presented to Steinman, Henry G. Kunkel Professor and head of the Laboratory of Cellular Physiology and Immunology, at a luncheon ceremony on Friday, September 28, in New York City.

Now in its 62nd year, the Lasker Award is the nation’s most distinguished honor for outstanding contributions to basic and clinical medical research. It has been given to 72 scientists who subsequently went on to receive the Nobel Prize, including 20 in the last 17 years. Nineteen other Lasker Award recipients are associated with The Rockefeller University.

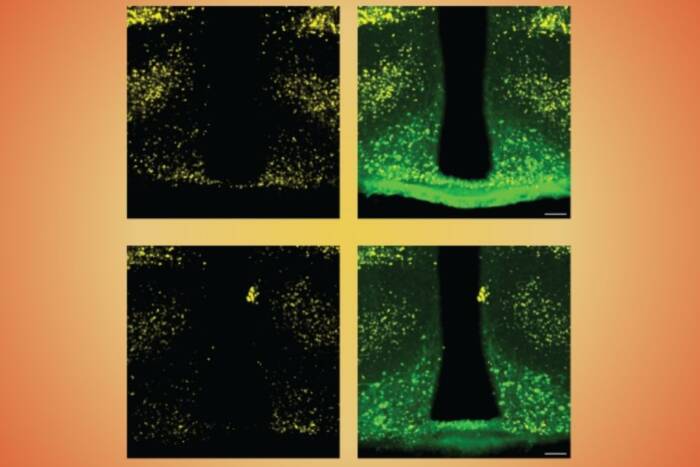

A cell's discovery. This image of a dendritic cell, one of the first ever made, was published by Steinman in 1974.

“Ralph’s extraordinary work over four decades has led to numerous groundbreaking discoveries about how our immune system works, and has generated leads that may someday help us win the battles against devastating diseases such as cancer, AIDS and autoimmune disorders,” says Paul Nurse, Rockefeller’s president, who has also been a Lasker recipient. “I am delighted to see his contributions recognized with this prestigious award.”

At a time when conventional wisdom pointed in other directions, Steinman proposed that dendritic cells propel other immune cells into action, and then pursued that possibility with careful and dedicated experimentation. He revolutionized our understanding of the events that instigate an immune response and unlocked the entire field of T cell activation. His work touches on all major facets of immunology and holds enormous clinical promise.

Steinman’s discovery of dendritic cells emerged from his efforts to better understand the function of how specialized immune system cells coordinate their responses. Working with the late Zanvil Cohn at The Rockefeller University in the 1970s, Steinman harvested a cellular mixture from mouse spleen that was known to spur T cells to divide in culture dishes. When he peered through the microscope at his spleen-derived substance, he noticed not only macrophages and other established immune cells, but rare, irregularly shaped cells that no one had described before. They moved in a distinctive way: Long projections emerged and floated around before retracting, giving the cells a dynamic star-like appearance. This branching behavior inspired Steinman to dub them dendritic cells, derived from the Greek word for tree. The cells differed from other immune cells in structure and behavior. For example, their surfaces didn’t carry molecules that typify macrophages, and they poorly internalized material from their environment. Unlike macrophages, they detached from plastic and glass culture dishes after growing overnight in the lab.

Over the following years, Steinman and his collaborators worked to better understand dendritic cells and to devise ways to harness them to direct the immune system to fight off tumors, viruses and other agents of disease. His research showed how dendritic cells scour the environment for microbial invaders and stimulate the T cells of the immune system to respond. These T cells in turn prompt other immune cells to eliminate the threat. Steinman devised techniques that generate large numbers of dendritic cells, which fueled a research boom in this area. His work spawned a major discipline, with hundreds of investigators worldwide studying these cells and their roles in multiple aspects of immune regulation.

In one area of research, scientists are working to teach dendritic cells how to identify and fight cancerous cells. In one version of this scheme, tumor cells are removed from an individual and delivered to dendritic cells from the same person in culture dishes. The dendritic cells are then injected back into the patient’s body in order to boost the immune system with cells whose primary mission is to attack that particular person’s tumor. Preliminary results are promising: The method shrinks tumors in experimental animals.

Recently, scientists have also been exploring strategies to create dendritic cell-based vaccines against pathogens such as HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. This line of investigation could prove especially fruitful, as HIV is particularly insidious with regard to dendritic cells. Steinman demonstrated that dendritic cells provide a safe haven for replicating HIV-1 and can transmit the virus to T cells. Thus, in the natural setting, dendritic cells help spread HIV-1 rather than quash it.

Because dendritic cells also help induce tolerance, the process by which animals learn to ignore their own cells, scientists are in addition working to adapt dendritic cells for clinical use in autoimmunity, allergy and transplantation medicine. These dual roles — of immune stimulation and silencing — bolster dendritic cells’ standing as a central modulator of the immune response.

Steinman received his undergraduate degree from McGill University in 1963 and his M.D. from Harvard Medical School in 1968. After completing an internship and residency at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, he joined Rockefeller University in 1970 as a postdoc in the Laboratory of Cellular Physiology and Immunology. He was appointed assistant professor in 1972, associate professor in 1976 and professor in 1988. In 1995 he was named Henry G. Kunkel Professor, and in 1990 he was appointed director of the Christopher Browne Center for Immunology and Immune Diseases. He is a member of the National Academy of Sciences and the Institute of Medicine.

The Lasker Foundation

Laboratory of Cellular Physiology and Immunology

Interactive media: How dendritic cells serve the body’s immune system as sentinels

Newswire: Dendritic cells stimulate production of immune-repressing T cells (September 14, 2007)

Newswire: Subset of dendritic cells could be used to fight infection (June 29, 2007)

Newswire: Targeting dendritic cells, HIV and malarial vaccines outperform competitors (March 7, 2006)

Journal of Experimental Medicine 137(5): 1142-1162 (May 1973)

Journal of Experimental Medicine 139(2): 380-397 (February 1974)

Previous Lasker Award winners at Rockefeller