A global view: Researchers build microRNA atlas

Building a comprehensive microRNA expression atlas is not easy. Just ask the Rockefeller University scientists who, in a massive collaborative effort involving 50 investigators from six countries, led the project. In three years, they catalogued microRNA expression patterns in more than 250 healthy and diseased cell and tissue samples – human and rodent – from 26 different organ systems, and in the process discovered several dozen new microRNAs as well.

“We wanted to provide a general overview of microRNA gene expression profiles for as many tissues as we could afford to test,” says postdoc Pablo Landgraf, lead author of the study. With the increasing number of studies addressing the role of microRNAs in diseases, particularly cancer, this database provides scientists with a starting point for more intensive study of individual microRNAs and how they contribute to disease.

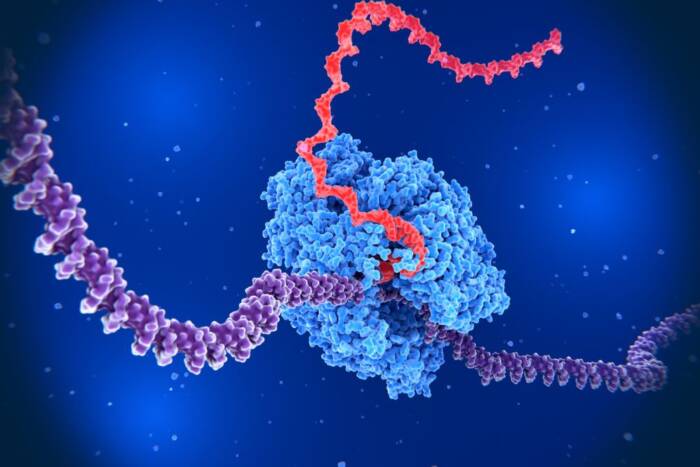

MicroRNAs are small noncoding RNAs found in animals, plants and viruses that regulate gene expression by destroying messenger RNA or interfering with its function. Scientists have identified many microRNAs in humans and rodents, but the expression levels and specificities of most of these microRNAs are not well characterized.

“There was a lot of confusion surrounding microRNAs – where they are expressed and at what levels,” says Thomas Tuschl, Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator and head of the Laboratory of RNA Molecular Biology, where Landgraf completed his work.

Tuschl and Landgraf first cloned and identified which microRNAs were expressed in all the tissue samples. By counting the total number of cloned microRNAs in each sample, they then tracked the expression levels of the microRNAs and compared their relative abundance in each. The collaborators provided the cell lines and tissue samples and organized the data for analysis. All in all, 97 percent of the microRNA clones they sequenced originated from fewer than 300 of the about 500 human microRNA genes.

This work not only clarified the specificity and the relative abundance of different microRNAs in more than 250 samples but found that most microRNAs are expressed ubiquitously throughout all cells and tissues. The researchers were also able to characterize the relative few that are expressed in particular cell types. For example, they found that blood cells predominately express five specific microRNAs, and that some blood cell types – like granulocytes – express microRNAs that other blood cell types do not.

In the process of creating these microRNA libraries, Landgraf and his colleagues also discovered several previously unidentified microRNAs, including 18 in humans, 27 in mice and 19 in rats. Most of these newly cloned microRNAs are expressed at low levels and half of them are not conserved across the three species.

“These low-level expressed microRNAs may provide a snapshot of microRNA gene evolution,” says Tuschl. “Out of the 500 human microRNA genes, only 300 of them are strongly expressed and regulation relevant; they show target sequence enrichment in mRNAs, whereas those expressed at low levels do not.” Since low-level expressed microRNAs have not yet left behind any sign of regulatory function on the genome, explains Tuschl, researchers who study microRNA function and disease association should focus on strongly expressed prototypical microRNAs.

The researchers also tested cancerous cells from patients with leukemias or lymphomas, which originate in B lymphocytes. Although they did not find a causal relationship between microRNAs and cancer, they did find that several microRNAs and their expression levels are associated with different cancers, raising the possibility that microRNA expression profiles could be used as diagnostic tools for discriminating among different types of lymphomas and leukemias.

This project began when Landgraf arrived at Rockefeller University more than three years ago. During the first year of his postdoc, he found that 20 microRNAs are strongly expressed within blood cells. But to determine which of these 20 are specific to these cells, he had to see which of these microRNAs are expressed in different tissues. “So,” says Landgraf, “we sort of just kept jumping from one tissue to the next.”

Cell 129: 1401-1414 (June 29, 2007)(opens in new window)