Viral detectives: Researchers track down the location of HIV-1 assembly in human cells

Since HIV was discovered in the early 1980s, scanning electron microscopes have been capturing images of the virus associated with different membranes of the cell they’ve infected. They can be seen stuck to the cell’s outer plasma membrane, as well as within membrane-enclosed structures called endosomes inside the cell. As a result, scientists couldn’t agree on where HIV particles were assembling: Many thought that they were being made in the endosomes, which transported them to the plasma membrane to be released, but others couldn’t reconcile that theory with the fact that partially assembled particles had been observed at the plasma membrane.

Now, in a new study published recently in PLoS Biology, scientists at Rockefeller University and the Aaron Diamond AIDS Research Center show conclusively that — contrary to the widely accepted endosome hypothesis — the HIV particles or “virions” are built at the plasma membrane. Paul Bieniasz, associate professor and head of the Laboratory of Retrovirology, postdoctoral associate Nolwenn Jouvenet and Professor Sanford M. Simon, head of the Laboratory of Cellular Biophysics at Rockefeller, used a number of different methods to trace the location of virion assembly, including an hour-by-hour assay to determine how long it takes the virus particles to appear in different parts of the cell.

(opens in new window)

(opens in new window)

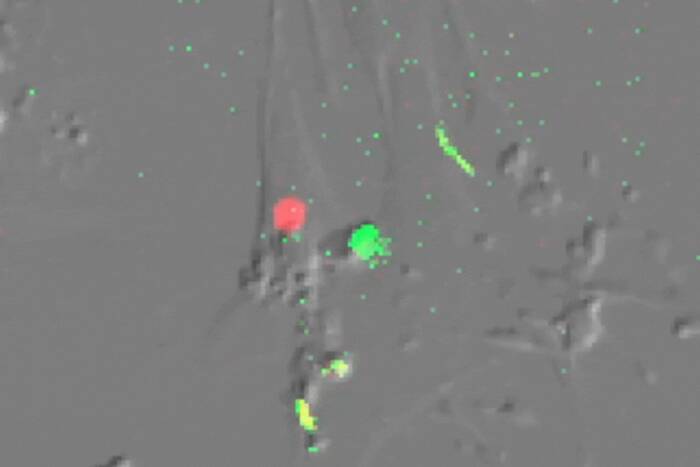

Dead end. When the researchers forced HIV-1 assembly to occur only on endosomal membranes (red), viral particles (green) appeared only inside the endosomes and were not released into the extracellular environment. This indicates that HIV particle assembly could not be initiating at the endosomes.

The Gag protein is the major structural protein of HIV-1, and just its presence is enough to elicit the production of virus-like particles. Jouvenet and Bieniasz induced cells to make fluorescently labeled versions of Gag, then disrupted structures that the endosomes use to move around inside the cell. If Gag were only being produced in the endosomes, freezing them in place would have prevented the viral particles from reaching the plasma membrane and leaving the cell. But freezing the endosomes didn’t have any noticeable effect on HIV-1 particle assembly or release.

Next, the researchers engineered the Gag protein so that it went directly to the endosomal membrane, bypassing the plasma membrane completely. But although forcing it to go there resulted in the assembly of many HIV particles inside endosomes, there was no measurable virion release into the environment outside the cell. “This,” says first author Jouvenet, “shows that the endosomal pathway is a dead end.”

The third group of experiments allowed the scientists to see Gag’s location in the cell at different points in time. Bieniasz and Jouvenet expressed the fluorescently labeled Gag in human immune cells called macrophages, then followed its progress through the cells over time. In previous experiments, Jouvenet says, “When people looked at macrophages, they looked really late, several days up to two or three weeks after infection. So we decided to look really early. And after just a few hours we can see virus particles forming.” Gag was assembling into viral particles at the cell’s plasma membrane first, only accumulating inside the cell’s endosomes about 24 hours later.

“We think that the virus is targeting the plasma membrane, some of the viral particles are released, and then the ones that are not released quickly are re-absorbed by the cell and end up in late endosomes,” Jouvenet says. In non-immune cells, they’re absorbed through a process called endocytosis; in macrophages, the researchers showed that the viral particles are taken up by a similar pathway known as phagocytosis.

Thinking back to the first images of the viral particles perched on a cell’s plasma membrane, Bieniasz notes that it was only later on that scientists attached significance to virions they saw in the endosomes and began to believe that the virus was assembled there.

“Simply because many viral particles can be seen in endosomes does not mean that’s where they assembled” he says.

PLoS Biology 4(12): 2296-2310.(opens in new window)