When ant colonies get bigger, new foraging behavior emerges

An ant scout leaves a trail of pheromones so his nestmates can easily find their way to the feast.

Millions of army ants occasionally stream out of their nest in a coordinated hunting swarm, seeking prey to devour. How this extraordinary mass raiding behavior evolved has long been a mystery, until now.

In a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences(opens in new window), Rockefeller’s Daniel Kronauer, together with graduate student Vikram Chandra and postdoctoral associate Asaf Gal, determine that mass raiding originally emerged from a similar form of organized hunting conducted by ant colonies, known as group raiding.

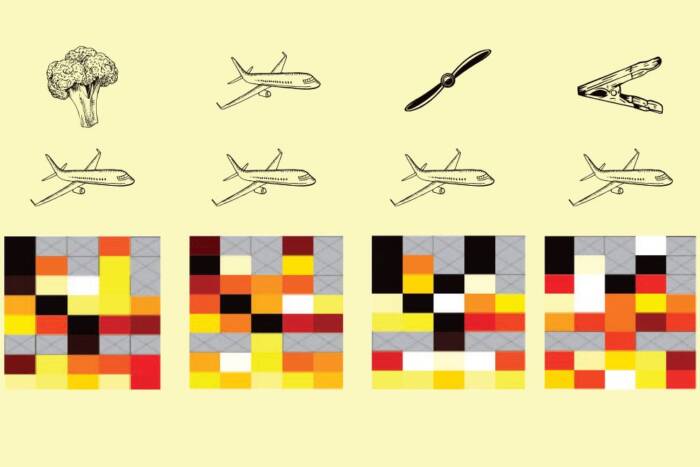

Group raiding is a foraging strategy practiced by ant species, such as clonal raider ants, which live in much smaller colonies than army ants. As the above video shows, individual clonal raider ants leave the nest to scout for prey. Upon discovering some grub, a scout heads back to the nest, leaving a trail of pheromones behind that its fellow ants can follow to the feast. The research team wondered whether army ants were following similar patterns, albeit on a larger scale, when mustering for their ravenous mass raids.

In order to answer that question, the scientists focused on clonal raider ants, which are easier to study in the lab than army ants. By increasing the size of raider ant colonies bit by bit, they were able to observe how the ants’ group raids began to gradually resemble that of army ants’ mass raids. That observation, coupled with analyzing the evolutionary relationships between species, led them to conclude that army ant mass raiding likely evolved from scout-initiated group raiding over tens of millions of years in concert with the enormous increases in colony size.

“This work is a nice insight into how collective behaviors evolve,” says Kronauer. “More generally it shows that you don’t have to alter an individuals’ neural circuitry to encode a new behavior—collective behaviors can evolve from simple scaling effects.”