Evan Heller

(opens in new window)Evan Heller

(opens in new window)Evan Heller

Presented by Elaine Fuchs

B.A., Columbia University

Forces Generated by Cell Intercalation Tow Epidermal Sheets

in Mammalian Tissue Morphogenesis

Evan Heller contacted me shortly after he was accepted to Rockefeller’s Ph.D. Program, and inquired about a possible rotation in my lab. He received his bachelor’s degree from Columbia, where he worked in the laboratory of Mike Sheetz, whom I know very well and works on scientific problems that are similar to our own lab interests. From our early discussions about science, it was clear that Evan was going to do well in our graduate program here. In watching his progress throughout his Ph.D., my favorable impression only continued to strengthen. Like many of our students here at Rockefeller, Evan has a powerful intellect, and is extremely talented at the bench. Yes, Evan is hard-working too. He also has a very positive attitude and he is one of the best liked people I’ve ever had in my laboratory.

So why did it take Evan so many years to complete his dissertation? It wasn’t from lack of productivity, as Evan’s thesis research, published in Developmental Cell, was termed a tour de force by his reviewers, who had glowing remarks about his work and have predicted that the work will be a landmark in the field. Many have since praised this paper. Evan was also instrumental in his contributions to our whole-genome wide screens in mice for oncogenic regulators and tumor-suppressors of growth. And he was instrumental in our screens for self-renewal factors in stem cells. And he was instrumental in our studies on aging in skin. And in our studies on planar cell polarity in skin development. In fact, Evan was an invaluable contributor to six major papers published during this time. One insight surfaces when I tell you that these contributions were entirely at Evan’s initiative, rooted in his broad curiosity and passion for science, not just his own but also those around him.

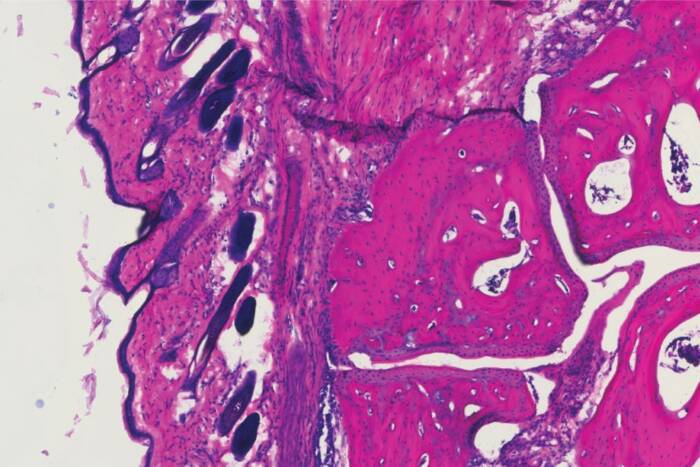

Another insight surfaces when I tell you that Evan’s Ph.D. thesis was not on skin, stem cells or cancer, the mainstream topics of my laboratory. Rather, Evan chose to focus on the molecular mechanisms underlying how the eyelids form during embryonic development. In mammals, our eyes form before we develop eyelids. Prior to Evan’s interest in the problem, no one understood how this happens. Is it localized proliferation at the border of the eye? Is it active migration? Is it a contractile mechanism, analogous to a purse string mechanism of closure? Evan showed that in fact the epithelium locally reshapes, expands and undergoes a collective movement over the eye. Evan showed that this process of cellular sheet movement is distinct from all the speculative models that were suggested at the time, and in fact different from all known mechanisms of cellular movements that were previously described, whether in wound-healing, or in fly or worm development. Evan showed that forces generated by cell intercalations at the border of the eye are leveraged to tow the surrounding tissue over the eye to form the eyelid.

To sleuth his way through the mechanism, Evan used live imaging of the process, laser ablation and quantitative analyses of tissue deformations, several other cell and biophysical strategies and some classy genetics. To choose a problem such as this one required fearlessness and passion; to solve the problem necessitated setting up the project from scratch, acquiring a diverse molecular toolbox of skills and crafting experimental strategies when no blueprint existed.

So in devoting this time to his thesis research, Evan has become a true scholar of biology. His depth of thinking is profound and his creativity and originality is exceptional. And all along the way, Evan has maintained his upbeat personality and honed his passion for science and collaboration. In my view, Evan is the perfect example of what our university strives for in developing the best and brightest minds in science.