Newly discovered immune cell partially responsible for psoriasis

In a discovery that may help shape new treatments for psoriasis, scientists at Rockefeller University have found a new type of immune cell that may be critical in producing inflammation and tissue damage in the skin.

(opens in new window)

(opens in new window)

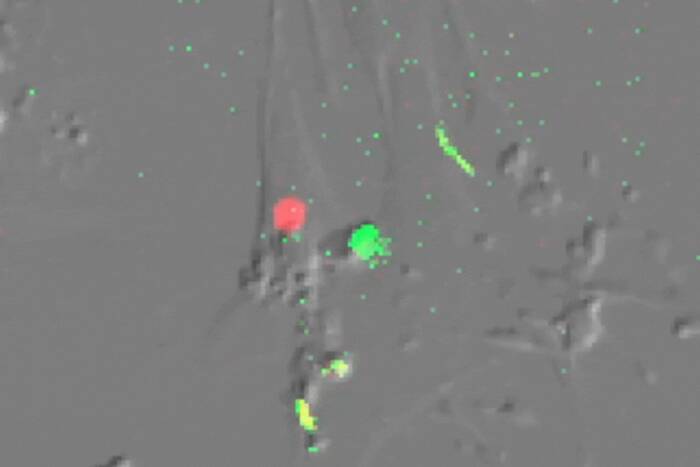

TIP off. In a sample of skin taken from a patient with psoriasis, yellow and orange areas indicate the presence of iNOS- (top) and TNF-producing (bottom) dendritic cells, known as TIP DCs. Rockefeller researchers believe this type of immune cell, never before seen in humans, may be responsible for inflammation and tissue damage in the skin of psoriasis sufferers.

Psoriasis occurs when white blood cells react to an unknown trigger and inappropriately launch an immune attack, causing red, scaly, inflamed skin lesions. During clinical trials of an extant psoriasis drug, James Krueger, head of Rockefeller’s Laboratory for Investigative Dermatology, and Michelle Lowes, an instructor in clinical investigation in the lab, in conjunction with Ralph Steinman, head of the Laboratory for Cellular Physiology and Immunology, noticed that a group of specialized dendritic cells seemed to be especially abundant in the affected patches of skin. When the researchers investigated, they found that these dendritic cells were producing two compounds known to be directly involved in immune reactions: tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS).

Dendritic cells that produce these compounds (“TIP DCs,” as the researchers call them), had previously been observed only in mice. Normally, dendritic cells coordinate the immune system’s response to foreign invaders. But as Kreuger and his colleagues write in a recent issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a number of clues point to the accumulation of TIP DCs as a major player in the onset of psoriasis: Psoriasis activity appears to be closely correlated with the presence of TIP DCs; TNF and iNOS both contribute to skin lesions; and efalizumab, a known psoriasis drug, causes the cells to decline.

Although many drugs have been approved to treat the condition, they’re rarely fully effective. “Quite commonly, the FDA will approve a drug if it’s shown to be safe and efficacious,” Lowes says. “But they don’t really need to know how it works. So, we try and put all of that together and figure out what the mechanism might be.” Now, after watching the effects of efalizumab on TIP DCs, Lowes believes that these cells may be an important target for future therapies.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 102(52): 19057-19062 (December 27, 2005)(opens in new window)