The art of tracking invisible patterns in animal behavior

Video Player

Anyone stepping into a gallery featuring Maximilian Pruefer’s(opens in new window) work might mistake the intricate patterns on the walls for imagery from a scientific symposium. The 38-year-old German multimedia artist has spent years capturing the unseen movements of animals, rendering their invisible world visible. Using innovative techniques, he records fleeting interactions—most recently, those of ants—transforming their behavioral traces into striking visual compositions.

The pursuit of uncovering hidden narratives in nature brought him to The Rockefeller University, where he spent six weeks in the Laboratory of Social Evolution and Behavior as an artist-in-residence. The lab is led by Daniel Kronauer, the Stanley S. and Sydney R. Shuman Associate Professor, who studies the evolution of complex insect societies, using ants as a model to explore how social behavior is regulated—from genes and neural circuits to colonywide interactions. The two were introduced by a mutual friend, and Kronauer immediately saw a connection.

“When I first saw Max’s work, I was struck by how closely it resembled the behavioral tracking we do in the lab,” says Kronauer. “We’re asking different questions, but both of us are interested in how collective behavior creates patterns.”

Decoding Ant Societies

Kronauer’s lab specializes in clonal raider ants, a species that reproduces asexually— producing genetically identical offspring without a partner—and relies on chemical communication rather than sight. These ants also exhibit social parasitism, a phenomenon in which some members of a colony exploit the labor of others. A decade ago, queen-like mutants unexpectedly emerged in the lab—ants born with wings, larger eyes, and reproductive abilities, showing no inclination to work. Their arrival provided new clues about how species evolve to become socially parasitic.

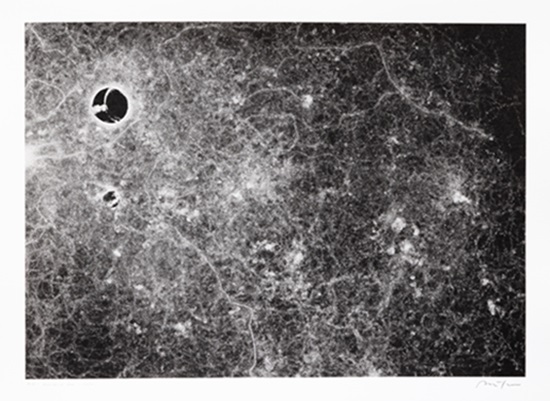

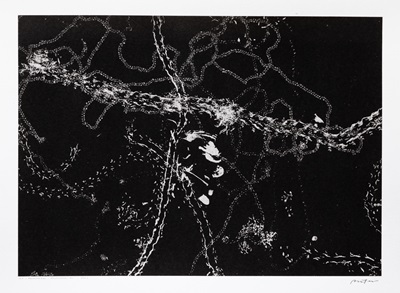

In the Kronauer lab, Pruefer placed entire colonies of clonal raider ants on his canvasses and allowed them to move over these surfaces for hours or even days. “In the end, it’s like a narrative of their movements and what they’ve done over the that whole time” says Pruefer, who has been experimenting with this technique for over a decade.

Pruefer was particularly intrigued by how these ants respond to chemical signals, especially alarm pheromones, which trigger a collective reaction to danger. Working with lab members, he designed a series of “art experiments” to make these responses visible. He placed ants on specially coated plates and introduced the distress signal, capturing their frantic escape routes as they scrambled in response.

“It was different from anything I’d done before,” Pruefer says. “I was watching an entire colony react to alarm and mapping the little streets they created as they left their nest.”

Where Art Meets Science

Beyond his work with ants, Pruefer explored other scientific tools during his residency. Rishika Mohanta, a second-year graduate student, introduced him to optogenetics, a technique that uses light to manipulate neural activity.

Pruefer hosted a workshop for graduate students attending the 2024 session of the Social Evolution and Behavior course taught by Daniel Kronauer at the Millbrook Field Station. The students set up “art experiments” where ants and termites walked across Pruefer’s specially prepared canvasses, weaving a tapestry of tracks with different shapes and patterns.

“I showed him how we can use light to create fictive smells for fruit flies,” Mohanta explains. “They reacted as if the odor was real, congregating around where they thought it was strongest.” Inspired by this, Pruefer is now considering ways to incorporate optogenetic techniques into his art practice and plans to exhibit the collaborative ant works in Germany later this year.

For the lab, the collaboration proved equally enriching. Over the years, Pruefer has developed novel coating methods to track the movements of various animals, from slugs and bees to flies and ants. Kronauer was immediately intrigued by these techniques, which complement the lab’s own tracking methods.

“Artists and scientists both have to develop new tools to explore abstract ideas,” says Kronauer, who hosts artists in each session of his Social Evolution and Behavior course taught at the Millbrook Field Station, as well as routinely invites artists for short lab visits to engage with students and postdocs informally. “An artist may find new inspiration from talking to scientists and understanding their techniques, and scientists can learn a lot from artists in return.”