A scientist’s 30-year quest reveals why a fat-sensing hormone can lose its effectiveness, leading to obesity

Jeffrey Friedman and Kristina Hedbacker, research associate, were first authors, as was Bowen Tan (pictured below). (Credit: Lori Chertoff/The Rockefeller University)

In 1994, Jeffrey M. Friedman discovered a hormone that monitors our body’s fat cells and signals our brain when it’s time to eat. Because animals become obese when this hormone is missing, he named it leptin, after the Greek for “thin”. In the decades since, tens of thousands of papers have built on his finding, exploring the hormone’s effects from multiple angles.

Much was learned, yet the answer to one fundamental question proved elusive: Why is it that, despite the presence of large amounts of the hormone, the brains of most obese patients cease responding to the “stop eating” signal sent by leptin? This resistance to leptin underlies 90% of cases of obesity, and to date scientists have been unable to pinpoint a cause despite decades of research.

Now, 30 years later, Friedman’s laboratory has finally located a neural mechanism in leptin-resistant obese mice that helps explain leptin resistance. At the same time, they also reported a means for reversing it using rapamycin, a drug commonly prescribed to prevent transplant rejections that’s also being explored for its potential as an anti-aging treatment.

We spoke to Friedman about the findings and their implications for improved obesity treatments.

You identified leptin resistance back in the ’90s, soon after discovering the hormone itself. What have you just learned about how dysregulated leptin leads us to put on pounds?

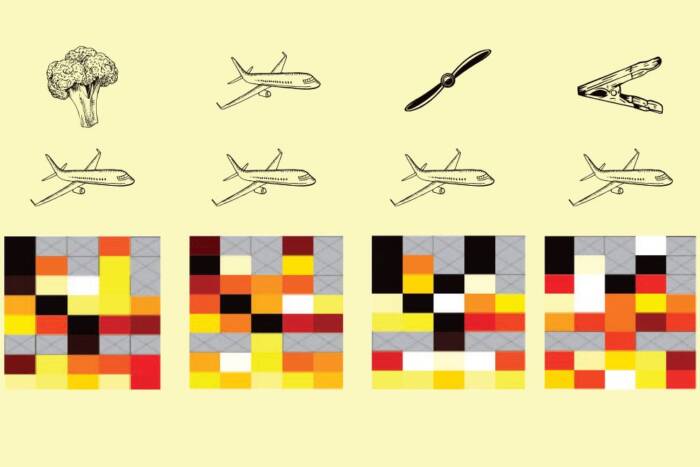

Scientists knew that leptin normally activates a population of neurons in the hypothalamus that express a gene known as POMC, and that mutations that interfere with the function of these neurons cause obesity. Recently, we found that leptin resistance in mice can result from increased activity of a signaling molecule called mTOR in POMC neurons, which in turn blocks leptin’s effects.

Rapamycin is a known mTOR inhibitor, and treating diet-induced leptin resistant mice with this agent restored leptin sensitivity. They ate less and lost weight—interestingly, the weight they lost was primarily fat, which is a characteristic of leptin treatment. This is significant because recently developed GLP-1 agonists that are helping so many people lose weight cause loss of both fat and muscle.

So your study also suggested a possible way to reverse leptin resistance. Do you think your lab’s work could lead to new treatments for obesity, much as research into GLP-1 agonists did?

Bowen Tan, first author. (Courtesy of Bowen Tan)

One of the problems associated with rapamycin treatment is that it can trigger diabetes. We found however that administering a dose of leptin with it mitigates the pro-diabetic effects of rapamycin in mice. Our finding that a leptin-rapamycin combination had a beneficial effect on glucose metabolism raises the possibility there could be a role for a combination of the two to reduce weight without the development of glucose intolerance. Testing this would require clinical studies, which are a bit premature. I prefer to think about immediate next steps. Right now, we’re very focused on the science. We’ve made an interesting set of observations, and we’ll see where they take us. For one thing, we’d like to understand whether additional neural cell populations other than the POMC cells contribute to the rapamycin response; mTOR is expressed in many places throughout the body. We would also like to develop means for inhibiting it specifically in POMC neurons. To that end, we’re investigating whether POMC neurons express a specific complement of mTOR components that might allow us to develop cell-specific mTor inhibitors. That would be preferable to the non-cell-specific inhibitors that are currently available.

In light of everything you’ve learned about obesity in the past 30 years, what do you most wish people better understood about it?

Research over the last three decades has shown that obesity is a biological disorder and not a result of lifestyle or poor dietary choices. The available evidence tells us that obesity is an endocrine disorder, which can result from either making too little of the hormone or developing resistance to it. The classic example of this is diabetes: If you have too little insulin, you have Type 1 diabetes, and if you become insulin resistant, you have Type 2. Similarly, patients with too little leptin lose weight on leptin therapy, but in those with acquired resistance, plenty of the hormone is present, but response to it is attenuated. This new understanding, together with the development of new biologic agents to treat obesity, make it clear that this disorder is not a personal failing. It’s time for the stigma associated with obesity to end.