New understanding of B cell mutation strategies could have implications for vaccines

(Credit: F8 studio/Shutterstock)

A vaccine’s ability to generate long-lasting, high-affinity antibodies hinges on a delicate balance. Upon exposure to a vaccine or pathogen, B cells scramble to refine their defenses, rapidly mutating in hopes of generating the most effective antibodies. But each round of this process is a roll of the genetic dice—every mutation has the potential to improve affinity; far more often, however, it degrades or destroys a functional antibody. How do high-affinity B cells ever beat the odds?

New research now suggests that B cells avoid gambling away good mutations by strategically banking successful ones. As described in Nature(opens in new window), successful high-affinity B cells can proliferate under special conditions that reduce risk of mutation. Capturing this mechanism in the lab may lead to more efficient vaccine strategies in the clinic.

“Our work shows how high-affinity B cells can bank really advantageous mutations by essentially cloning themselves rather than continuing to mutate,” says co-first author Julia Merkenschlager, who led the work as a postdoctoral fellow in Michel C. Nussenzweig’s Laboratory of Molecular Immunology at Rockefeller and is now a member of the faculty of immunology at Harvard Medical School. “Perhaps we will soon be able to tailor vaccines to tip the scales either toward mutation or cloning.”

The downsides of evolution

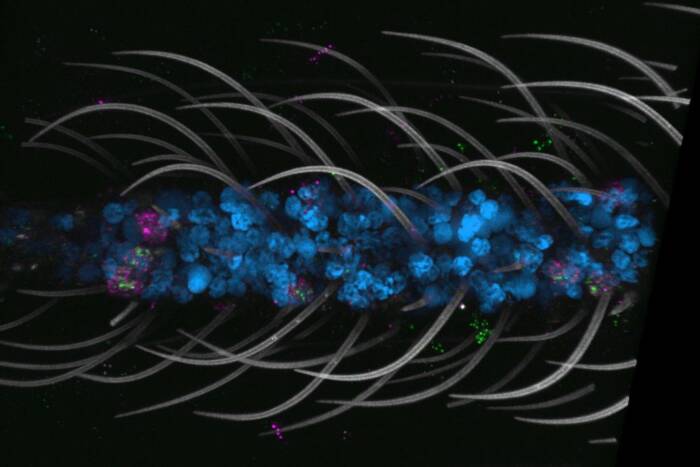

Vaccines and infections lead to the construction of germinal centers, specialized immune structures where B cells mutate and mature. Germinal centers rapidly introduce mutations into an otherwise average army of B cells but, since mutagenesis is random, the probability of B cells acquiring worthless or deleterious mutations far outweighs the chance they’ll acquire mutations that enhance their affinity for an antigen. In addition, the mutator enzyme makes targeting mistakes in the genome that can lead to translocations and cancer. These errors are responsible for most human B cell lymphomas.

As a consequence, high-affinity B cell lineages should frequently degrade. Yet studies have repeatedly shown that germinal centers produce high-affinity antibodies with remarkable efficiency. The existing model suggested, improbably, that B cells essentially win the lottery again and again, even while risking everything on the next ticket.

“If we’re imagining that antibodies get better over time through a process like Darwinian evolution, there should be negative consequences too,” Merkenschlager says. “But that math doesn’t add up.”

Unless the game is rigged. The team suspected that the system had a safeguard—some way for high-affinity B cells to pause mutating and hold onto their best traits. The question was how that safeguard worked. And in vaccine development, the answer to that question would be a game changer. If scientists could figure out how the immune system shifts from randomly generating antibodies to stabilizing its best ones (and avoiding cancer producing mistakes) that knowledge could be harnessed to create vaccines that extend the “gambling” phase—mutating repeatedly to generate highly evolved antibodies for difficult targets, such as HIV—or accelerate to the “banking” phase to preserve effective antibodies.

Different strategies for different outcomes

Merkenschlager and Nussenzweig therefore teamed up with theoretical physicists at Princeton to use agent-based models to simulate this mathematical conundrum and shed new light on the issue. They started by mapping B cell lineages with single-cell RNA sequencing, to determine whether various populations of B cells were, in fact, mutating.

They discovered that high-affinity B cells divided more frequently but underwent fewer mutations per division. Previous research from the Nussenzweig lab had shown that B cells proliferate rapidly when aided by T cells, but the effect on mutation rates remained unclear. The team found that this additional support accelerated high-affinity B cells through the cell cycle, shortening their time in the G0/G1 phases—where hypermutation occurs. Meanwhile, B cells that had not yet won the jackpot continued to roll the dice with drawn-out G0/G1 phases and baseline assistance from T cells.

The findings were confirmed in mouse immunization studies involving model antigens as well as exposure to the receptor-binding domain of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. “We learned that there are two mechanisms: diversify and clone,” Merkenschlager says. “Weaker B cells can diversify, with extended hypermutation. Higher-affinity B cells can clone, copying those traits so they can proliferate without fear of deleterious mutations.”

Both findings may have significant implications for vaccine design. Broadly neutralizing antibodies against HIV, for instance, require extensive hypermutations to have any hope of latching onto that elusive virus, which constantly mutates and hides key targets under a sugar-coated shield. An ideal HIV vaccine would therefore extend the mutational phase before allowing clonal expansion, ensuring that only B cells with the highest affinity antibodies win out—a strategy that has, until now, been out of reach. But first, the team will focus on validating the findings in humans and determining whether vaccine adjuvants or other strategies can tilt the balance between gambling and banking.

“Now that we have an idea of how to control what a cell will bank versus what it will gamble, we can begin to think about how to design a more effective vaccine,” Merkenschlager says.