Study implicates 60 genes in congenital heart disease, including some that also contribute to related disorders such as autism

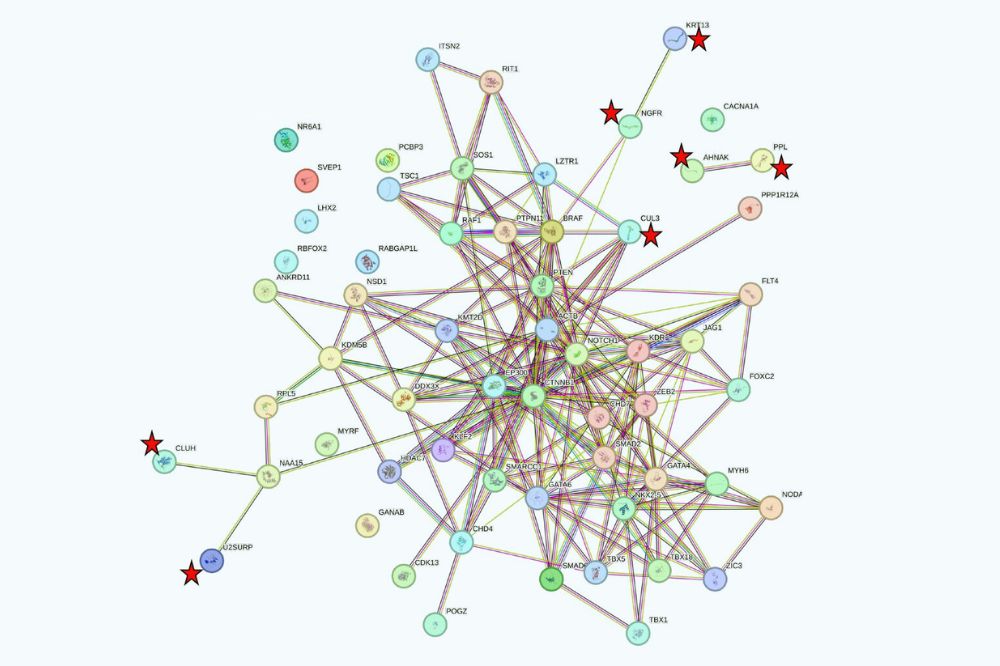

STRING analysis of 60 significant genes in CHD. Genes not previously implicated in human CHD that have at least one edge are denoted by red star. (Courtesy of Lifton lab)

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is one of the most common birth defects, but the full extent of its genetic underpinnings has been a mystery. Now, a new study of more than 11,000 children with CHD identifies 60 genes that are mutated in CHD patients more often than expected by chance.

The study is part of the Pediatric Cardiac Genomics Consortium, a multi-institution effort funded by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of NIH to identify the genetic causes of CHD and to understand the relationships between genetic factors, clinical features and outcomes in individuals with CHD. Published in PNAS(opens in new window), the findings reveal a complex genetic landscape—more than half of the genes identified were linked to a specific heart defect, such as tetralogy of Fallot; mutations in others produced a variety of CHD subtypes as well as neurodevelopmental disorders including autism. Some mutations occurred spontaneously (de novo), while others were inherited from clinically unaffected parents. The results provide new insight into the genetic architecture of CHD, and have implications for how physicians conduct prenatal screening and early risk assessment.

“Many of these results are surprising, and have implications for families,” says Richard Lifton, senior author of the new study. He is head of the Laboratory of Human Genetics and Genomics and President of The Rockefeller University. “These findings provide new insight into the complex biology of heart development. Moreover, with this information, physicians can screen children with CHD for the genetic cause to clarify diagnosis, prognosis and risk of CHD in subsequent children.”

Casting a wider net

The PCGC previously found evidence that new (de novo) mutations account for about 9 percent of CHD, but few specific genes had been identified. The 60 genes now implicated account for about 60 percent of this signal. In addition, surprisingly, another 5 percent of cases are attributable to mutations transmitted from parents who most frequently do not have clinically apparent CHD. Another paper from the PCGC published earlier this month, also showed that recessive mutations, which only cause disease when both copies of a gene are mutated, contribute to only about 2 percent of CHD cases.

“We were surprised by how infrequently recessive genotypes contribute to CHD in our cohort,” says senior author Martina Brueckner, Professor of Pediatrics and Genetics at Yale University. “The exception is that children who were the offspring of consanguineous union were nearly 7-fold more likely to have recessive causation of CHD, and that children with CHD associated with abnormal development of left-right body asymmetry were over-represented among the group with recessive gene mutations.”

Interestingly, 10 of the 60 genes implicated in the current study are involved in chromatin modification. These include mutations in genes that encode enzymes that covalently modify histone proteins and/or recognize the modified histone proteins. “Histone modification was implicated in the regulation of gene expression by the late C. David Allis at Rockefeller,” Lifton adds. “The frequency of mutations in this pathway in CHD as well as in autism and other congenital diseases is testimony to the importance of Allis’s discoveries.”

Surprises and screenings

A surprise in this study was that about half the genetic contribution in this study came from mutations transmitted from parents, rather than de novo mutations. In most, but not all instances, the parents did not have clinical CHD. In some families, subsequent children from the same parents have inherited the same mutation and have CHD. Nonetheless, the magnitude of the risk is uncertain. The frequent observation of incomplete penetrance (e.g., parents with the mutation without CHD) suggests that either additional genetic or environmental factors may play a role in disease causation.

The team also discovered that 33 of the genes had strong associations with a single CHD subtype, while others contributed to a broad spectrum of heart diseases. Mutations in the NOTCH1 gene stood out for its variability—mutations that altered cysteine amino acids required for normal folding of repeated segments of the gene called EGF domains, were strongly enriched in patients with tetralogy of Fallot, and other conotruncal defects, which affect the outflow tracts of the heart, while truncating mutations in Notch1 contributed to an much broader set of CHD phenotypes.

“Mutations in some genes almost always produce one form of heart disease, like clockwork,” Lifton says. “Why others can give you virtually many of the major forms of CHD remains a mystery for now.”

As striking was the discovery that 37 of the CHD genes are strongly predictive of associated neurodevelopmental disorders, including autism, while others are not. Some of these same genes have been independently implicated in autism and neurodevelopmental disorders. With the help of Rockefeller’s Junyue Cao, head of the Laboratory of Single Cell Genomics and Population Dynamics(opens in new window), the team found that mutations in genes such as MYH6 almost never produce associated extracardiac features, and are virtually exclusively expressed in the heart or the linings of the blood vessels during development, while those linked to disorders in many organs are broadly expressed in many cell types, including those in the brain.

These findings have a number of clinical implications. For instance, the lessons learned may influence screening protocols for certain neurodevelopment disorders. “Early intervention may be able to improve outcomes in autism.” Brueckner says. “Because CHD is evident at birth, physicians may be able to use what we learned in this study to identify high risk kids in the first weeks of life, well before appearance of neurodevelopmental problems, and while the opportunity to intervene is greatest.”

The results also highlight the potential utility of for routine genetic screening in CHD patients. While all individuals studied had been already diagnosed with CHD, about one-third carried mutations in genes known to be associated with additional pathologies that characterize well-known syndromes; many of these children were not clinically diagnosed—often because they lacked one or more characteristic features of those syndromes. Without genetic testing, neurodevelopmental disorders and potentially treatable later onset heart problems such as arrhythmias may not be considered.

“In the overall costs of caring for children with these severe forms of CHD, which typically require surgical intervention and other care, the rapidly lowering price of DNA sequencing to determining the genetic profile is becoming a negligible contribution,” Lifton says. “But the potential advantage of making these diagnoses early is that physicians will be able to anticipate problems—and hopefully intervene to achieve better outcomes.”