Wrong Proteins Targeted in Battle Against Cancer?

Lasker recipient James E. Darnell contends drug developers should focus more on “transcription factor” proteins

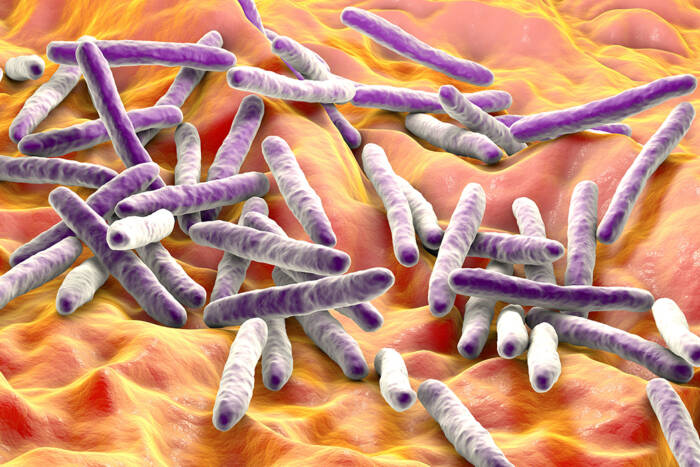

The image above shows how two STAT3 molecules — proteins that are known to be overactive in many human cancers — come together to form one functional complex, also called a "dimer." In the Oct. issue of Nature Reviews Cancer, James. E. Darnell argues that drugs designed to block the protein-protein interactions characteristic of dimers like this one potentially could be used to treat a variety of cancer types.

Researchers may be looking for novel cancer drugs in the wrong places, says Rockefeller University Professor James E. Darnell Jr., M.D., in an article in this month’s Nature Reviews Cancer.

Darnell, who received the 2002 Albert Lasker Award for Special Achievement in Medical Science, argues that drug development research should focus more on a specific group of proteins — called transcription factors — known to be overactive in almost all human cancers.

“The facts indicate that a limited number of transcription factors are indeed overactive in many cancers and that these overactive proteins themselves are appropriate drug targets,” says Darnell, head of the Laboratory of Molecular Cell Biology at Rockefeller and co-author of the popular textbook Molecular Cell Biology.

These transcription factors include STAT3, discovered by Darnell and colleagues in 1994, STAT5, NF-kappaB, B-catenin, Notch, GLI and c-JUN — all of which play significant roles in a wide variety of cancers.

According to Darnell, drug developers continue to largely ignore these seemingly universal molecules of cancer because, unlike other cancer-causing proteins called protein kinases, transcription factors do not posses “active sites” or pockets that can be easily fitted with small inhibitory drugs.

Instead, drugs designed against transcription factors would have to target protein-protein interactions — which, because of their larger surface areas, are much harder to disrupt.

Still, Darnell argues that, despite inherent obstacles, such an approach potentially could yield novel cancer therapeutics.

“After all,” he asks, “What is the benefit to medicine in all the 21st century promise of proteomics if we cannot selectively inhibit protein-protein interactions?”

Many of the transcription factors involved in cancer normally allow a healthy cell to respond to signals from the external environment by activating the “expression” of certain genes, which then leads to the production of new proteins. In cancer — which is characterized by cell growth gone awry — genetic mutations cause these proteins, also referred to as “oncogenic proteins,” to become unusually active.

Therefore, drugs designed to block or decrease their surplus activity might effectively treat this disease.

“Transcription factors are attractive targets both because they are less numerous than other signaling activators and are at a focal point of many cancer pathways,” says Darnell.

“Like kicking Achilles in the heel, striking at these targets would constitute a more global approach to fighting cancer.”

In the past, drug developers in search of cancer therapeutics have focused largely on cancer-causing molecules called protein kinases, primarily because their active sites — tiny crevices where small molecules normally bind and activate the protein — easily can be blocked with small molecule drugs. The drug Gleevec, for example, can temporarily treat chronic myeloid leukemia by fitting into and plugging up the active site of a protein kinase, called the Ableson kinase, associated with this disease.

But, according to Darnell, this approach has two main drawbacks. First, as is the case with Gleevec, resistance to the drugs can develop; second, each of the protein kinases tends to be associated with only a limited number of cancer types.

Darnell believes that both of these obstacles could possibly be overcome by instead targeting certain transcription factors. He argues that these proteins should not develop resistance to drugs as fast as protein kinases, and, because they are common to many cancers, drugs designed to block them should work against a diverse range of cancer types.

The final challenge is then how to target molecules that lack the convenient active sites of protein kinases. Drugs directed against transcription factors would have to prevent them from binding to one of their two primary molecular targets: DNA or proteins. To turn on specific genes, transcription factors must bind to other proteins as well as to DNA.

Since past efforts to develop drugs that disrupt DNA-protein interactions have failed, Darnell believes that targeting protein-protein interactions is the next logical step.

“With the availability of robotic screening procedures, huge chemical libraries need to be screened for small molecules that target any of the specific protein-protein interactions of transcription factors,” he says.

“Even though this approach is more difficult,” he adds, “It has proved practical in one preliminary case, and furthermore many inventive technologies from chemistry labs around the world give hope that this approach has great possibilities.”