Rockefeller researchers provide the first functional evidence for mammalian pheromone receptors

Pheromones — chemical signals that influence social and reproductive behaviors — have been studied since the 1950s, but the molecules in the mammalian nervous system that actually detect pheromones have remained elusive.

Now, a team of researchers, led by The Rockefeller University’s Peter Mombaerts, M.D., Ph.D., provides the first functional evidence for molecular receptors for pheromones in mammals. Their findings contribute to our understanding of the functioning of the brain in orchestrating social and reproductive behavior. They also may help explain why sexual reproduction typically occurs only within a species and, ultimately, how species form.

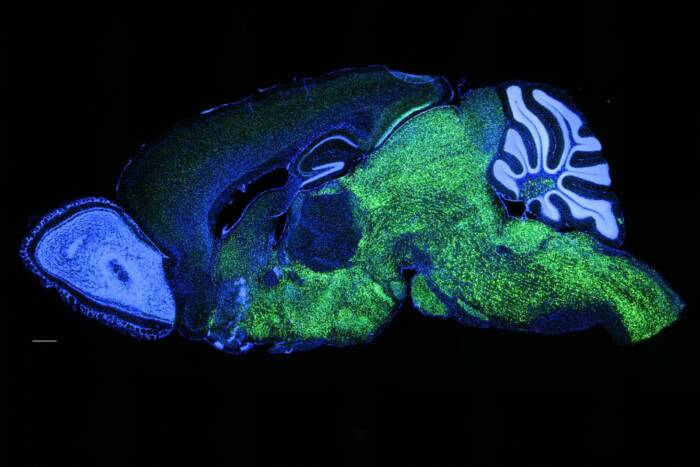

In the Sept. 5 issue of the journal Nature, Mombaerts and colleagues at Rockefeller, University of Maryland School of Medicine and Monell Chemical Senses Center report significantly less aggressive and sexual behavior in laboratory mice who were engineered to lack a particular cluster of genes that previous research from the Rockefeller lab had linked to pheromone detection. They also show that the nerve cells of mutant mice are unable to detect certain pheromones. These pheromone receptors are found in the lining of the animals’ vomeronasal organ (VNO), a part of the olfactory system thought to be specialized in the detection of pheromones.

“We know that the VNO is involved with pheromones because if it is surgically removed from the animals, several abnormalities in their mating behavior and aggression patterns arise,” says Karina Del Punta, the lead author on this paper and a graduate student at The Rockefeller University.

“We found that deleting the cluster of genes that produce pheromone receptors replicates some aspects of the surgical removal of the VNO in these animals.”

The researchers used a sophisticated technique of genetic manipulation called “chromosome engineering technology” to delete a region of 16 genes from the genome of the mouse. The mutant mice developed normally, were fertile and were indistinguishable from normal or control animals with respect to their general behavior.

However, the mutant males and females displayed clear differences in aggression and sexual activity compared to their normal counterparts.

Normally, nursing females are aggressive toward other lab mice that intrude or invade their nest. The nursing mutant females, however, were less aggressive when confronted by an intruder: there were fewer attacks, the first attack was delayed, and the total time spent attacking the invader was much less, when compared to the behavior of the females’ normal counterparts in the same test situation.

The researchers studied four behaviors in the male mutant mice, and found two of these to be affected in the mutant mice. A first assay tested if male mutants emit 70 kilohertz ultrasounds when first exposed to a female. Removing the VNO reduces this behavior, but in the mutant mice it was unaltered. Second, male aggression against other males was also unchanged in the mutants.

A third test focused on male-male sexual behavior. Socially inexperienced mice are often observed to exhibit sexual behaviors toward other males until they become more experienced and learn to distinguish males from females. Socially inexperienced mutant mice, surprisingly, made fewer sexual advances toward males, suggesting that the mutants are better at distinguishing between sexes without prior experience, or that their sexual drive overall is reduced.

The fourth behavioral test analyzed sexual behavior of males toward females, which is also dependent on a functioning VNO. Compared to their normal counterparts, the mutant males tended to mount females fewer times, and the more they were exposed to females, the less they mounted.

Normally, male and female mice that spend time together engage sexual behavior with each other. This gain of sexual activity through experience does not occur in mutant mice, and it is consistent with reports from other researchers who have removed the VNO from male mammals.

When the nerve cells in the VNO of the mutant mice were exposed to mouse pheromones, the team discovered that certain pheromones no longer elicited a physiological response in these cells. Other pheromones, however, still stimulate these nerve cells, indicating that the sensory deficit is specific. The authors coined a new term for this selective chemosensory deficit: a specific avnosmia, analogous to specific anosmias to certain ‘common’ odorants reported in many cases over the past decades, both in mouse and human. “The specific avnosmia may perturb the normal detection of pheromones and cause the behavioral abnormalities we observed,” speculates Del Punta.

Whether a functional VNO is present in humans is controversial. The role of pheromones in human behavior also has not been clearly defined. The Mombaerts team had shown earlier that the human genome harbors 5 putative pheromone receptor genes that could be functional. The genome of the mouse, by contrast, has at least 140 receptor genes of this type, and the mutant strain of mice described in the Nature paper misses precisely 16 of these.

“Our work has shown for the first time that these are pheromone receptors in mice. This in turn will stimulate research in functional characterization of the counterparts of these genes in human,” concludes Mombaerts.

Mombaerts’s co-authors are Karina Del Punta, Ivan Rodriguez, David Jukam and Sonoko Ogawa at Rockefeller; Trese Leinders-Zufall and Frank Zufall at University School of Medicine, Baltimore; and Charles J. Wysocki at Monell Chemical Senses Center.

This research was supported in part by the National Institute of Deafness and Communicative Disorders, part of the federal government’s National Institutes of Health; the March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation, and the Swiss National Foundation for Research.