Conor Liston

A.B., Harvard University

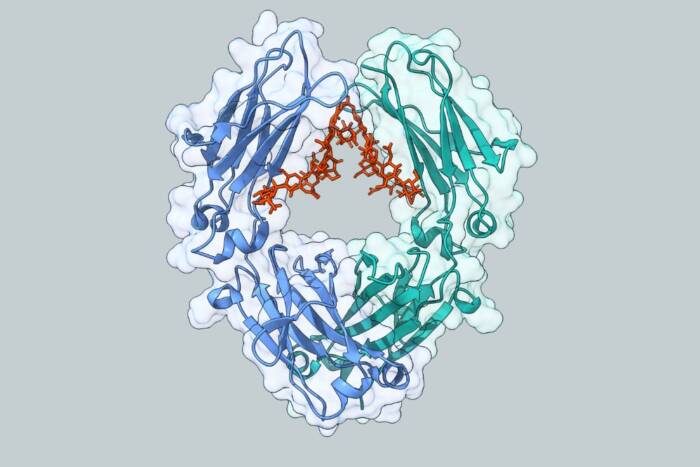

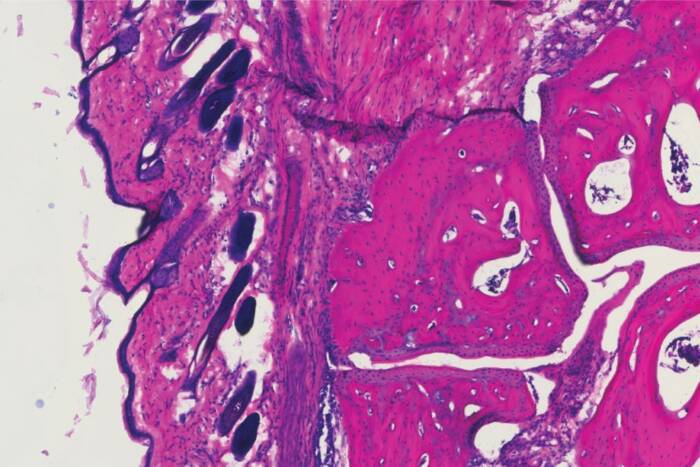

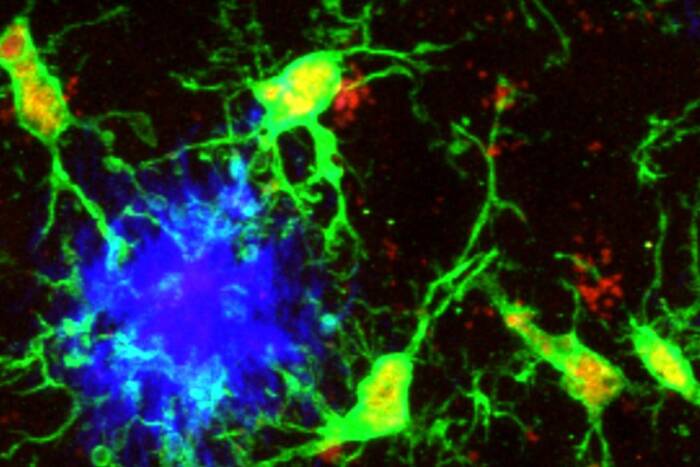

Chronic Stress Effects on Prefrontal Cortical Structure and Function

presented by Bruce S. McEwen (on behalf of himself and B.J. Casey)

Conor Liston was born in San Diego and grew up in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. He went to Harvard University, where his undergraduate majors were psychology and biology, and he graduated in 2002. His research as an undergraduate with Jerome Kagan on memory development in children resulted in his senior thesis that led to summa cum laude recognition upon his graduation and a first-authored paper in Science. Conor entered the Tri-Institutional M.D.-Ph.D. Program right after graduation and did a rotation with B.J. Casey, at Weill Medical College of Cornell University, on diffusion tensor imaging of white matter tracts in childhood and adolescence. His second rotation was with Charles Gilbert to study visual processing. He then joined our laboratory and established a very fruitful collaboration with Dr. Casey on the effects of stress on the brain, in which he studied stress in an animal model (the rat) and also in medical students (another animal model). Dr. Casey is his co-mentor and joined me in preparing this presentation.

Conor found that stress causes nerve cells in the rat brain to shrink in the prefrontal cortex, a brain region that is responsible for mental flexibility. The stressed rats showed decreased mental flexibility. Armed with this information, Conor worked with Dr. Casey to define a brain circuitry in the human prefrontal cortex that is activated by a similar test of mental flexibility like the one he used in his rat model that was published in Neuron last year. To do this, he used functional brain imaging, a wonderful method that allows neuroscientists to study the human brain noninvasively. He then studied some of his fellow medical students preparing for their medical licensing examinations, finding that some students were more stressed out than others. The students who were the most stressed showed impairment of their mental flexibility and displayed a slowing down of the neural circuits that mediate mental flexibility. But is this brain damage? The good news is that these deficits were not permanent. After the exam and a month off, the mental flexibility had recovered and so had the neural circuits. Conor’s work reinforces the idea that our brains are more resilient than we give them credit for.

Conor’s co-mentor, Dr. Casey, writes, “The best descriptions I have for Conor are ‘passionate’ and ‘persistent.’ He has an extraordinary passion for science. Even during his medical training, you would still find him in the lab at night getting a fix. He can’t seem to get enough. He is also one of the most persistent scientists I’ve met, following up on every question. He really did complete about three dissertations! I feel very lucky to have had the opportunity to work with him and luck means a lot to the Irish.” At present, Conor is completing his medical studies and continuing his research, showing his incredible energy, passion and ability. To Conor’s parents, we offer special congratulations and appreciation for having Conor with us — to his mother, Marion, his father, Michael, and younger brother, Emmet.