Sexual behavior pathways in the brain identified

Valentine’s Day cards usually depict Cupid’s dart as the messenger of love. New scientific research, however, shows that a key messenger molecule, rather than Cupid’s dart, is responsible for female sexual receptivity–at least in rats and mice.

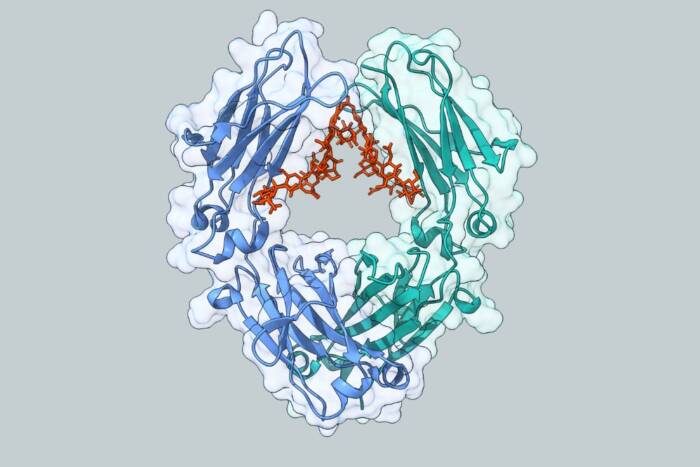

Scientists at New York’s Rockefeller University and Houston’s Baylor College of Medicine have found that a protein called DARPP-32 is the essential ingredient in the brain pathway that makes female mice and rats sexually receptive. The study is reported in the Feb. 11 issue of Science.

“Abnormalities in signaling by the neurotransmitter dopamine are associated with several neurological and psychiatric disorders, including Parkinson’s disease, schizophrenia, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and substance abuse,” says Paul Greengard, Ph.D., Vincent Astor Professor and director of the Fisher Center for Research on Alzheimer’s Disease at The Rockefeller University. “We had shown earlier that DARPP-32 is a major player in the mechanisms by which dopamine produces its effects in the brain.

“Our new studies, which were carried out in collaboration with Shaila Mani, Ph.D., and Bert O’Malley, Ph.D., at Baylor College of Medicine, suggest that DARPP-32 plays a key role in a novel signaling system in the brain which is involved in the regulation of sexual behavior,” he continues. “Numerous studies over the past few decades have provided evidence for interactions between the nervous and endocrine systems, and the present data on DARPP-32 provide a molecular basis for the mutual interdependence of these two systems in sexual behavior.”

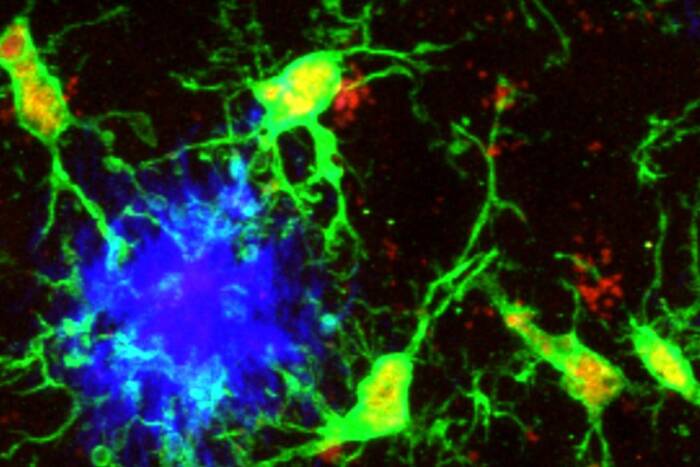

Researchers already knew that female sexual behavior is influenced by two categories of intercellular signals: nerve transmitters (such as the pleasure-related chemical dopamine) produced by the brain and sex hormones (such as progesterone and estrogen) produced by the ovaries.

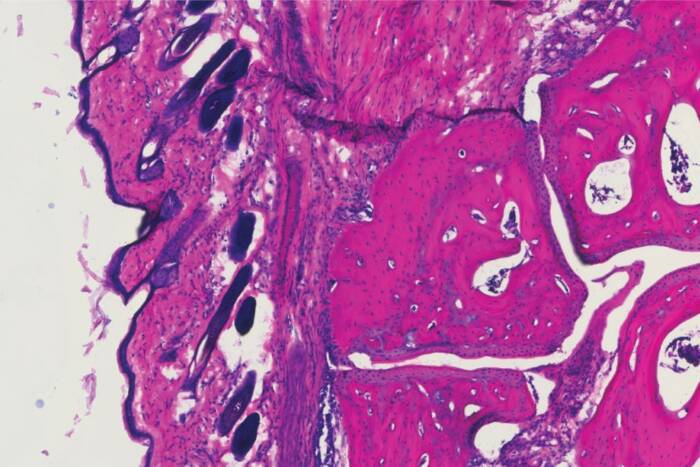

The new research looks at the intersection between these two factors. The DARPP-32 protein is found in the nerve transmitter pathway in the brain’s hypothalamus and is also needed in the brain pathway controlled by progesterone. Without DARPP-32, the signals that normally prompt sexual behavior are not sent, and the sex hormones have no effect.

For the study, the researchers used both genetically engineered mice that lacked DARPP-32 and rats whose DARPP-32 was inactivated. After the ovaries were removed to stop the production of sex hormones, the mice and rats lost all interest in sex and even fought aggressively with approaching males. Injections of estrogen and progesterone did not reverse the behavior, because the hormones were ineffective without DARPP-32.

The new research shows that the pathway through which sex hormones travel in the hypothalamus merges with the nerve-transmitter pathway where dopamine travels. This critical intersection requires DARPP-32.

Developing drugs that intervene in these pathways may alter sexual response and may be a way to regulate behavior, says Mani, the lead author on the Science paper.

“This research provides a model to study complex behavior,” says O’Malley, chair of molecular and cellular biology at Baylor and senior investigator of the Baylor group. “It’s likely that other brain pathways and hormones interact similarly to produce other types of behavioral responses.”

Other authors on this paper are Andrea Mitchell, Ph.D., at Baylor and Pramod Dash, Ph.D., at the University of Texas-Houston Medical School. This research was funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and by the National Institute of Mental Health.