Gene Involved in Brain Development Identified

Astrotactin is a Nerve’s Ticket to Ride the Glial Highway

Scientists from The Rockefeller University and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute(opens in new window) (HHMI) have for the first time identified a gene involved in directing nerve cells to their destinations as the brain grows. Their work appears in the April 19 Science.

“The gene we discovered makes a protein, astrotactin, required for young neurons to migrate along glial fibers to find their correct positions in the growing brain. This journey is important because it is the way young neurons gain their identity,” says Mary E. Hatten, Ph.D., head of the Laboratory of Developmental Neurobiology at Rockefeller. “Knowing the gene’s function could lead to a greater understanding of epilepsy, a condition people can be born that we think occurs because of problems with neuron migration.”

Hatten and her coauthors’ findings also may shed light on the development of childhood brain tumors, learning disabilities, schizophrenia and degenerative brain disorders in the elderly. Already, researchers know that exposure to alcohol, cocaine and radiation can hinder the migration of neurons during fetal development.

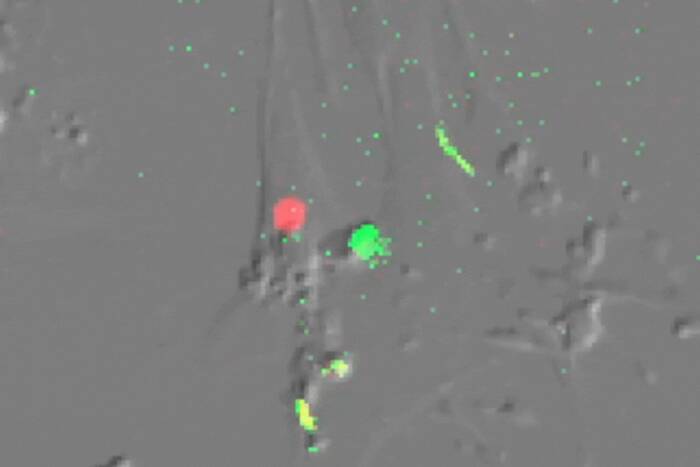

This four part photograph shows the movement of a young nerve cell on a glial fiber highway at 18, 40 and 63 seconds. This journey, of about one thousandth of an inch, helps a neuron find its correct position in the growing brain. [Photo: Mary E. Hatten, Ph.D.

In the new study, Hatten and her colleagues found a gene, Astrotactin, in the neurons of mice that contains the instructions to make the astrotactin protein. Neurons use the protein, which Hatten discovered, to grab hold of fibers in the developing brain and move along them.

The migration of neurons is critical to survival. During the development of the fetus, cells form a tube that will grow into the brain and spinal cord. After cells are born, they move through the tube’s thickening wall to form the layers of what will be the cortex, the brain’s outer layer known as gray matter. By completing this journey the neurons develop and organize into the brain’s architecture.

The migration of young neurons in the brain’s cerebellar cortex, which controls movement and balance, continues until a child reaches the age of two. Although a neuron’s journey along the glial fiber highway is just a few millimeters, this distance is comparable to a person traveling from New York City to Chicago, Hatten says. The nerve cells can migrate at speeds of 20 to 50 microns per hour– about one thousandth of an inch, which is considered fast for a neuron.

In addition the cerebellum, the researchers pinpointed active Astrotactin genes in the brain’s cortex, hippocampus and olfactory system, responsible for thinking, memory and smelling.

Hatten and her coinvestigators also identified a second function of astrotactin. “The astrotactin protein helps glial cells to sustain their health and identity,” explains coauthor Nathaniel Heintz, Ph.D., head of the at Rockefeller and an HHMI investigator. “Without a connection to astrotactin, the glial cells collapse. In contrast, astrotactin is not essential to maintaining the health of neurons.”

With the cloning of the Astrotactin gene, the research team proposes that at least three genes play a role in the migration and assembly of neurons during the development of the cortical areas of the brain in mice: the Astrotactin gene, the Weaver gene and the Reeler gene. However, Weaver and Reeler occur as the result of mutations and they interfere with migration. Weaver prevents astrotactin production in the neuron and Reelin disturbs the organization of neurons at the end of their migration.

Hatten and Heintz’s coauthor is Chen Zheng, B.S. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke supported the study. Hatten’s work also is funded by a McKnight Neuroscience Award.