Scientists discover gene mutation that causes children to be born without spleen

The spleen is rarely noticed, until it is missing. In children born without a spleen, that doesn’t happen until they become sick with life-threatening bacterial infections, often within their first year of life. An international team of researchers led by scientists from Rockefeller’s St. Giles Laboratory of Human Genetics of Infectious Diseases(opens in new window) has now identified the defective gene responsible for this rare disorder. The finding may lead to new diagnostic tests and raises new questions about the role of this gene in the body’s protein-making machinery.

Alexandre Bolze, a visiting student in Jean-Laurent Casanova’s lab, analyzed data from exome sequences to identify a defective gene that causes children to be born without a spleen.

Medically known as isolated congenital asplenia, missing spleens have been documented fewer than 100 times in the medical literature. Alexandre Bolze, a visiting student in the St. Giles lab, headed by Jean-Laurent Casanova, set out to identify the gene responsible for isolated congenital asplenia. He and his colleagues conducted an international search for patients, and identified 38 affected individuals from 23 families in North and South America, Europe and Africa.

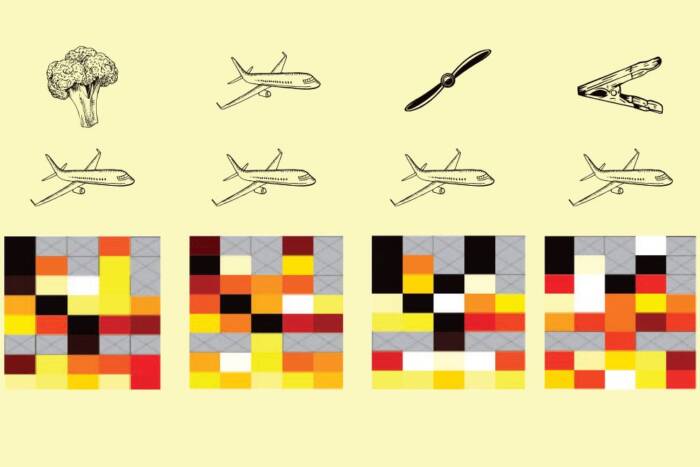

Bolze and his team sequenced the exomes – all DNA of the genome that is coding for proteins – of each of the 23 affected families. After filtering two public databases of genetic information for gene variations in controls, the researchers were left with more than 4,200 possible genes. To narrow this list of candidate genes further, Bolze hypothesized that the disease-causing gene would be more frequently mutated in the affected exomes than in control exomes. By cross-referencing the frequency of mutations against data from patients with other types of diseases, Bolze found one gene with high significance: RPSA, which normally codes for a protein found in the cell’s protein-synthesizing ribosome.

“These results are very clear, as at least 50 percent of the patients carry a mutation in RPSA,” says Bolze. “Moreover, every individual carrying a coding mutation in this gene lacks a spleen.”

The findings, Bolze says, are surprising because the ribosome is present in every organ of the body, not just the spleen. “These results raise many questions. They open up many research paths to understand the specific role of this protein and of the ribosome in the development of organs in humans.”

(opens in new window) (opens in new window) |

Science Express: April 11, 2013 Ribosomal Protein SA Haploinsufficiency in Humans with Isolated Congenital Asplenia(opens in new window) Alexandre Bolze, Nizar Mahlaoui, Bridget Turner, Nikolaus Trede, Steven R. Ellis, Avinash Abhyankar, Yuval Itan, Etienne Patin, Samuel Brebner, Paul Sackstein, Anne Puel, Capucine Picard, Laurent Abel, Lluis Quintana-Murci, Saul N. Faust, Anthony P. Williams, Richard Baretto, Michael Duddridge, Usha Kini, Andrew J. Pollard, Catherine Gaud, Pierre Frange, Daniel Orbach, Jean-Francois Emile, Jean-Louis Stephan, Ricardo Sorensen, Alessandro Plebani, Lennart Hammarstrom, Mary Ellen Conley, Licia Selleri, Jean-Laurent Casanova |