Physician scientist, interested in obesity-related disease, to join faculty

More than one in three U.S. adults is obese, a condition that puts them at risk for an alarming array of health problems, from diabetes and heart disease to cancer. But while obesity brings devastating consequences for many, some escape. For a select few, obesity causes little more than sore joints and fatigue, at least for a time.

Rockefeller’s newest faculty member, Paul Cohen, a cardiologist and molecular biologist, studies the origin of this discrepancy with the ultimate goal of developing treatments for obesity in its most harmful form. A Rockefeller alumnus, he joined the university January 1 and has established the Laboratory of Molecular Metabolism, where he will investigate the molecular basis for obesity’s role in metabolic diseases.

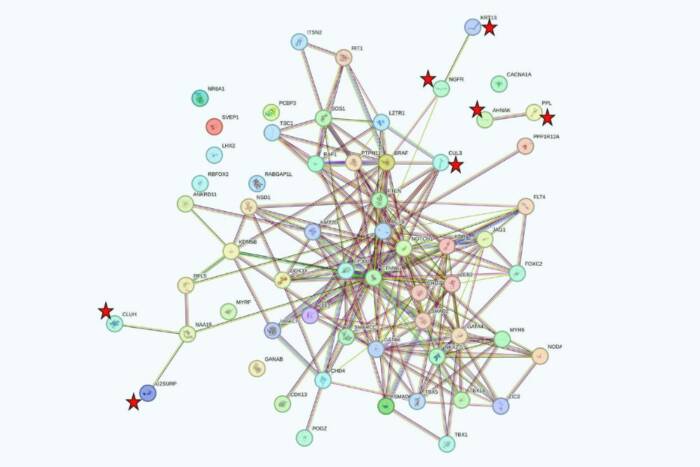

Previously a postdoc at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, an attending cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and an Instructor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School in Boston, Cohen did his graduate work at Rockefeller in Jeffrey Friedman’s Laboratory of Molecular Genetics. When Cohen joined Friedman’s lab in 1998 the group was following up on the discovery of leptin, working to determine how the hormone exerts its weight-loss promoting effect. Cohen found leptin repressed the production of a liver enzyme involved in fat metabolism. He and his colleagues concluded that this enzyme, SCD-1, acts as a regulatory switch to determine whether fat is stored or burned.

“This is a homecoming for me: Rockefeller is where I learned to be a scientist,” Cohen says. “With its focus on both basic and translational science, Rockefeller is the perfect place for a physician scientist who wants to do fundamental research on the mechanisms underlying human disease. I am looking forward to taking advantage of the amazing opportunities for collaboration with my new colleagues.”

Cohen earned his M.D. from Weill Cornell Medical College, through the Tri-Institutional M.D.-Ph.D. Program, and went on to specialize in preventive cardiology. He developed a clinical focus on the cardiovascular complications associated with obesity, and was impressed by the wide variation in the degree of disease obese patients experience.

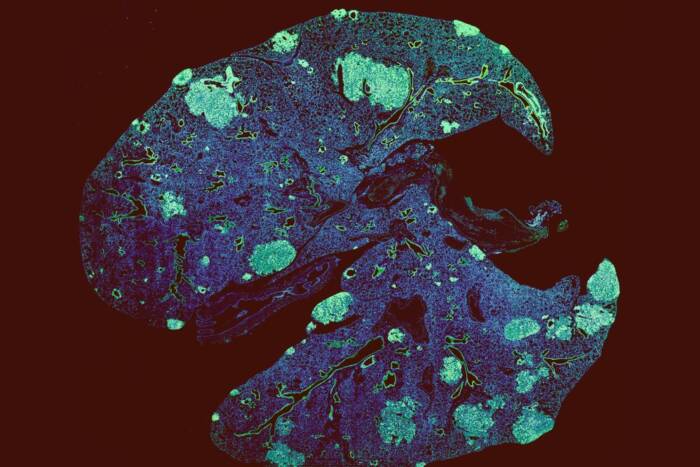

In order to begin to explain why, Cohen and others first had to take a close look at the different types of fat. White fat cells warehouse fat in large droplets, attracting inflammation and causing disease; fat stored within the abdomen, or visceral fat, contains white cells.

But fat can also have healthful effects. Found in infants and recently in small amounts in adults, brown fat cells evolved to maintain body temperature by burning the fat they store. Scientists have more recently found small deposits of a third type, beige fat. Located in clusters and surrounded by white cells, beige cells can burn calories just like brown fat cells when exposed to cold or to certain hormones. Beige fat cells are generally found subcutaneously, or in deposits under the skin.

Cohen’s postdoctoral research helped establish the health protecting effect of beige fat and identified a key role for the molecule PRMD16 in activating beige fat cells so they burn calories just like brown cells.

When looking at subcutaneous fat, the less detrimental type of deposit that contains beige cells, Cohen and his colleagues found significant levels of PRMD16, which was already known to help regulate the expression of RNA, the molecule that carries protein making instructions for DNA. They then genetically modified mice so they could not produce this molecule in fat cells. Without PRMD16, the beige cells could not burn calories and came to resemble white fat. Meanwhile, the mice became obese and developed problems related to obesity, including resistance to insulin, a precursor condition to diabetes. This raises the possibility of treating obesity-related conditions by turning on PRMD16 in fat cells.

Cohen is now working to better understand the molecular basis for the negative effects of visceral fat, and at Rockefeller he plans to use mouse models he has developed to uncover the specific connections by which fat tissue contributes to various disorders, such as high blood pressure.

“Paul’s work so far has made significant contributions to the understanding of metabolism, first through his work on the leptin pathway, and, more recently, by exploring the biology of fat cells,” says Marc Tessier-Lavigne, the university’s president. “As he works to build a research program based in molecular biology and biochemistry, and helps to develop novel treatments for obesity, Paul joins a long tradition of Rockefeller physician-scientists who combine studies of human subjects with laboratory and animal findings to push the boundaries of our knowledge. It is truly a pleasure to welcome Paul back to Rockefeller.”